This article was last updated on April 16, 2022

Canada: ![]() Oye! Times readers Get FREE $30 to spend on Amazon, Walmart…

Oye! Times readers Get FREE $30 to spend on Amazon, Walmart…

USA: ![]() Oye! Times readers Get FREE $30 to spend on Amazon, Walmart…

Oye! Times readers Get FREE $30 to spend on Amazon, Walmart…

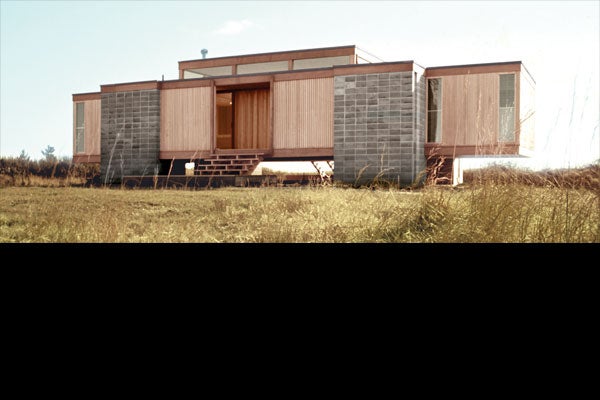

Five miles out from Long Island’s southern shore lies the narrow 30-mile long emerald sandbar known as Fire Island. While most locals today think of this little spit of paradise simply as the sleepier, campier, no-Range Rovers allowed alternative to the Hamptons, Fire Island has a far more interesting story to tell. Beginning in the late ‘50s, this secluded escape became the setting for major cultural and political shifts that would bring tumultuous and far-reaching transformations over the next two decades. From the mainland moral police came threats to the rising gay culture of Cherry Grove and the Pines, from mega-autocrat Robert Moses came threats of destroying the entire barrier island environment to make way for an expressway. Residents organized to fight for a way of life that preserved the natural dunescapes and forest preserves, and fostered outward expressions of freedom and liberation.

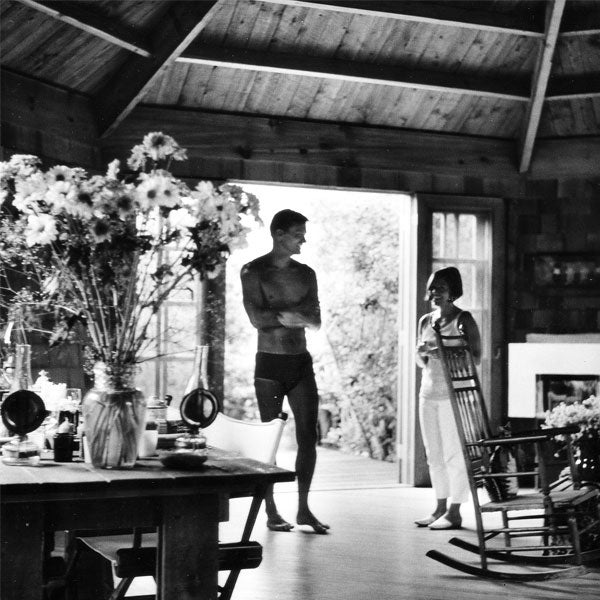

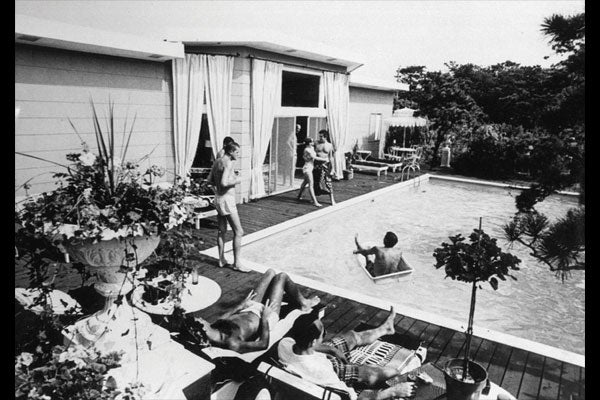

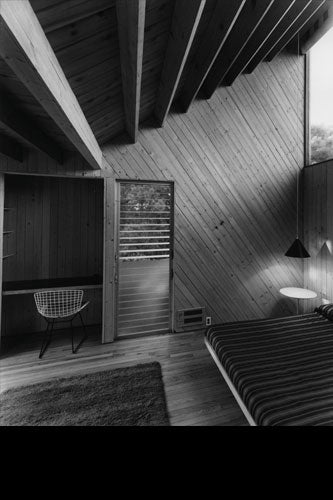

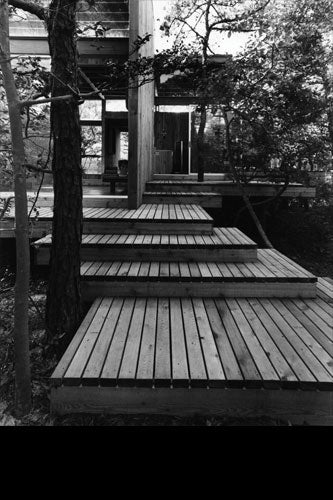

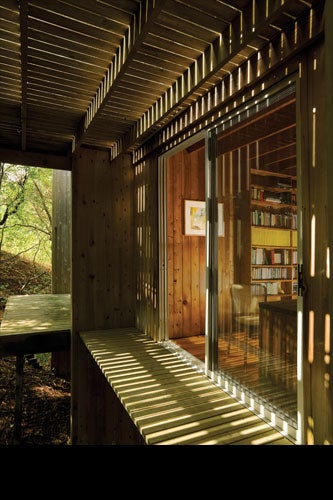

When Horace Gifford found himself for the first time in the Pines on Fire Island in 1961, this tempestuous and persuasive young architect impulsively bought a small plot of land and began to create what even he could never have anticipated, and no architect had really ever been able to achieve — the building of an entire community of modest yet expressive modernist houses. Often organized around a central, slightly exhibitionist social space that extended outdoors to one or more decks, these refined beach homes were highly attuned to the physical and social environment of Fire Island and only got more interesting during the cultural upheaval of the late ‘60s and ‘70s.

With the release of Fire Island Modernist, NYC-based architect Christopher Rawlins has discovered a new hero in local architecture. Not one for those typical dry analyses of architecture, Rawlins’ intimate writings bring us face to face with the events that shaped Gifford’s life and work, his deep commitment to a sustainable modern architecture, and his often turbulent life on Fire Island. By doing so, Rawlins reveals the humanity behind modernism, and is launching an effort to preserve a rare community of design that is in danger of being lost. Gifford advocated for an artful way of living simply and openly, and hoped that “someday we will learn to live with nature instead of living on nature.”

The following are just 12 of the more than 70 houses that Gifford created in the Pines and elsewhere on Long Island, in his prolific but tragically short life. They tell a story of a true talent coming into his own, and suggest a future we have yet to fulfill. Scroll through to get a “tour” of Gifford’s best Fire Island work and world…our own personal swan song to a New York summer.

Kevin Baxter: Your writing on Gifford blends personal details and social history with architectural analysis, something rarely attempted in architectural writing. What are the important lessons you take from his personal and professional life?

Christopher Rawlins: “Gifford’s life and career offers inspiration as well as a cautionary tale. Nowadays many prominent architects jet around the world creating isolated monuments. By focusing most of his efforts in one place, Gifford created that rarest of things–a community. But his life also illustrates that it takes more than talent to achieve lasting success. It also takes good health and a stable personal life. Gifford suffered in those departments, to the detriment of his career.”

KB: There’s a noticeable connection and warmth in your writings about Gifford — it is clear that you identify with him on many levels. How do you think your research on his work has influenced you personally as an architect?

CR: “During the depths of the Great Recession when I began to focus on this book, I felt that the profession was passing me by. Fussing over someone else’s career proved to be an agreeable distraction, and a slightly less narcissistic way of processing my feelings about success and influence. I have always gravitated towards architects like Carlo Scarpa and Rudolph Schindler; craftsmen on the fringes of high modernism who bent the movement to their own ends. Gifford certainly fits that profile, and practiced his craft in a place with which I identify deeply. Exploring Gifford’s houses, I remember thinking to myself “I wish I had worked for this man.” Fire Island Modernist is pretty much a fulfillment of that wish.”

KB: How has your discovery of Gifford altered your perspective and understanding of the Pines on Fire Island?

CR: “I didn’t originally come to Fire Island because of its gay communities, I came because I found the Hamptons too traffic-clogged and its social life too formal. Fire Island is basically a glorified sandbar with pedestrian-only enclaves, surrounded by protected dunes. The Pines offers natural beauty along with rather stunning examples of human beauty. This is a double-edged sword, since the Pines is often portrayed in the media as a shallow and body-obsessed place. But it’s not that simple. Gifford himself was physically beautiful, yet he conjured some of the most substantive architecture to appear on the island. As someone who resides on the island beyond the peak party weekends, I know it as a place where New Yorkers with small apartments get to enjoy a more communal, less harried existence in homes that they share with their friends. Gifford was very tuned into this communitarian impulse, and his grand public spaces surrounded by tiny bedrooms reflect that.”

KB: I have a personal obsession with discovering modern architecture on Long Island, and in the rare instance that I do spot a flat roof, it’s like spotting Bigfoot; I’m not sure if my eyes are deceiving me. I imagine your discovery of Gifford’s houses in the Pines must have felt like discovering a lost city. How many still exist, and what was that discovery process like?

CR: “I describe these houses as my “portal to a lost world.” Gifford often left the addresses off of his drawings, so it has been an ongoing hunt to discover the remaining homes in what is now a lushly forested place. He built 40 of his homes in the Pines, a few of which have been demolished. About a dozen are in original condition, while the rest have been altered to some degree. With original drawings at my disposal, faithful restorations can now be undertaken. In my capacity as a practicing architect, I am about to begin work restoring a Gifford home to pristine condition.”

KB: Few architects are as sensitive to emerging social developments, or were as enmeshed in their progress as Gifford was in the evolution of the Pines in the ‘60s and ‘70s. Do you see the social history of the Pines as inextricably linked to Gifford’s architecture? In short, can you imagine the Pines without Gifford, or Gifford without the Pines?

CR: “Given the clientele that was present in the 60’s and 70’s—I’m thinking of people like Halston, Angelo Donghia, and Calvin Klein—chances are that fancy homes would have dotted the Pines with or without Gifford. And there were certainly other, less prolific modernists at work in the Pines. But it is doubtful that such a coherent style of architecture would have emerged that everyone now recognizes as the Pines vernacular. Also, Gifford was a precocious environmentalist who tried to reduce the size of his homes. His rich clients lived in homes just slightly larger than his middle class clients. As he put it, “Someday we will learn to live with nature instead of living on nature.”

KB: The metropolitan sensibility Gifford brought to Fire Island perfectly framed the newly emerging social life of the Pines and the city dwellers gathering there to escape the dense city, and although his houses are serene, they were never boring. He could create a setting for a blowout party that would make most people blush, if not run the other way! Could Gifford have made such a unique architectural impact anywhere but Fire Island?

CR: “Gifford emulated a model established by Paul Rudolph in Sarasota, in which a young architect housed a sophisticated audience in a place that was slightly under the radar. I think the postwar period was rather unique, and Gifford came along during the last bloom of modernism. But I talk about how modernism was a pretty durable aesthetic for gays, whose own history made them less susceptible to the nostalgic appeals of Postmodernism in the 70’s. To this day, there are only a handful of Postmodern homes in the Pines. While Gifford succeeded in turning the Pines into a modernist utopia, he failed in a similar attempt to transform Galveston, Texas in the late 70’s.”

KB: You humbly acknowledge that you were not a writer before you took on this project. But I have to say, I could not put this book down, the writing and narrative are so sharp and immersive. How did this challenge shift your creative thinking? Do you now have aspirations for more writing projects on Gifford or others?

CR: “Thank you. The most satisfying part of writing Fire Island Modernist lay in transcending the limits of a typical architectural monograph and creating a more expansive social history. My next book may not be about architecture at all!”

KB: If you had a chance to speak with Gifford today, what might you ask him?

CR: “I would ask him what he thought of all this fuss. One of his close friends allowed that the usually wry and reserved architect would be grinning from ear to ear. That means a lot to me.”

KB: Long Island, and especially its beaches, was never thought of as a respectable architectural setting — I mean, can you imagine Mies stepping foot on a beach? What characteristics did Gifford possess that allowed him to bring such a sophisticated process to this setting?

CR: “Gifford was a sophisticated architect, but he was also a nature-loving boy from the rustic shores of Vero Beach, Florida who never entirely assimilated into what he called “the cosmopolitan attitude of New York.” He paired these two aspects of his personality to create structures which were somehow glamorous yet unpretentious.”

KB: In your opinion, what future environments, in or around New York City, lie undiscovered, perhaps awaiting a new Gifford to come along and create an architecture that is as suited to its social and physical environment as Gifford was to the Pines?

CR: “We are running out of land, but New York City’s rooftops await a visionary like Gifford to reconnect them, and us, with the natural world.”

KB: In your book, you point out Gifford’s many influences — particularly Louis Kahn and Paul Rudolph, giants in the field and two characters not easy to reconcile. Yet he never aped their work and was able to create his own structures enriched by, as you put it, a “complex genetic code.” What major architectural principles does Gifford have to teach us today?

CR: “Gifford found a way to be modest and provocative at the same time. His houses are small and light on the land, but they exhibit none of the dour, homespun artlessness that many people associate with environmentalism. In his hands, sustainability is sexy.”

KB: Now that you have single-handedly become the point man for Gifford’s work, you have created the Horace Gifford Project. What have been your hopes in establishing this?

CR: “Behind the breezy tone of Fire Island Modernist resides a passionate preservationist. I don’t believe that the houses can never be altered in any way, but it certainly helps to understand what makes these homes special before changes are contemplated. An archive will be established to house Gifford’s papers for both homeowners and scholars. With my friend Philip Monaghan, I am also creating a non-profit organization called “Pines Modern,” dedicated to the preservation of the homes and sensibilities that were honed in the Pines at mid-century. We’re kicking this off with a series of house tours that I am conducting later this Summer entitled “Modern Masterpieces: A Mid-century Tour of Fire Island Pines.” Here is the link:http://www.getresponse.com/archive/cbrawlins/11837662.html“

KB: Okay, last question, but perhaps the most challenging: Knowing these houses the way you do, and even having lived in one, tell us what is your favorite Gifford house and why?

CR: “That is a hard one, but I really love his second personal residence from 1965, which I rented for two summers. I consider it to be his first masterpiece. It’s a clutch of four shed-roofed towers, pin-wheeled around a flat-roofed breezeway with disappearing glass walls that shelter the living and dining areas. Birds fly through one side and out the other, never realizing that they’ve entered a building. Can there be any better test of architecture in harmony with nature?”

Click HERE to read more from Refinery29.

Be the first to comment