This article was last updated on May 27, 2022

Canada: ![]() Oye! Times readers Get FREE $30 to spend on Amazon, Walmart…

Oye! Times readers Get FREE $30 to spend on Amazon, Walmart…

USA: ![]() Oye! Times readers Get FREE $30 to spend on Amazon, Walmart…

Oye! Times readers Get FREE $30 to spend on Amazon, Walmart…

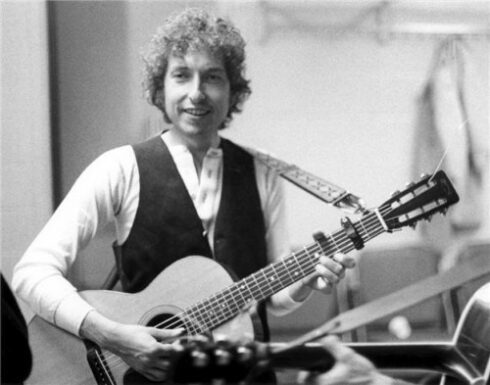

By Stephen Pate – Tangled Up In Blue from Blood on the Tracks is often cited as one of Bob Dylan’s greatest songs. The book A Simple Twist of Fate: Bob Dylan and the Making of Blood on the Tracks tells the story of how the perfected version of the song was recorded after Christmas 1974.

Tangled Up In Blue is a love song of epic proportions with bohemian lifestyle intertwined with shape shifting, time shifting and leaps from third person to first person without explanation.

The listener is taken on a wild ride from East to West from the North to Gulf Coast, as the protagonist wins the love of his life, loses her, finds her again for an idyllic interlude that is broken as reality intrudes again and the three lovers part. The true romantic, he never forgets her and he is on the road “got to get back to her somehow.”

If the original version was a fluid story, it has always remained that way as Dylan never stopped re-writing Tangled Up In Blue to suit his creative, artistic impulses.

At The Beacon Theatre in New York City in December 2014, Dylan re-wrote Tangled Up In Blue one more time “As Dylan segues into “Tangled Up in Blue,” I think of one of my favorite lines from it — “Some are mathematicians; some are carpenters’ wives/ Don’t know how it all got started; don’t know what they’ve done with their lives.” But, tonight he isn’t singing those words. He’s changing the lyrics: “Some of them are in the mountains,” he sings. “Some of them are down in the ground/ Some of their names are written in flames and some of them, they just left town.” (Adam Langer An Autobiography in 19 Dylan Concerts .

Tangled Up In Blue was originally recorded on September 17-19th, 1974 in New York City by Bob Dylan with accompaniment from Eric Weisberg and Deliverance.

But Dylan was not happy with the results and on December 30, 1974 Bob Dylan re-recorded the song with essentially a pick-up band in Minneapolis, Minnesota. That version is the one that transfixed us when Blood on the Tracks was released in 1975.

Kevin Odegard was the guitar player in the studio for the re-recording session and along with co-author Andy Gill he weaves the magic spell of one of Bob Dylan’s most magical recording sessions.

From A Simple Twist of Fate

At The Beacon Theatre in New York City in December 2014, Dylan re-wrote Tangled Up In Blue one more time “As Dylan segues into “Tangled Up in Blue,” I think of one of my favorite lines from it — “Some are mathematicians; some are carpenters’ wives/ Don’t know how it all got started; don’t know what they’ve done with their lives.” But, tonight he isn’t singing those words. He’s changing the lyrics: “Some of them are in the mountains,” he sings. “Some of them are down in the ground/ Some of their names are written in flames and some of them, they just left town.” (Adam Langer An Autobiography in 19 Dylan Concerts .

Tangled Up In Blue was originally recorded on September 17-19th, 1974 in New York City by Bob Dylan with accompaniment from Eric Weisberg and Deliverance.

But Dylan was not happy with the results and on December 30, 1974 Bob Dylan re-recorded the song with essentially a pick-up band in Minneapolis, Minnesota. That version is the one that transfixed us when Blood on the Tracks was released in 1975.

Kevin Odegard was the guitar player in the studio for the re-recording session and along with co-author Andy Gill he weaves the magic spell of one of Bob Dylan’s most magical recording sessions.

From A Simple Twist of Fate

Clearly pleased with the results of the earlier session, DyIan seemed more relaxed this time, at ease with his accompanists, and open to suggestions. He produced a small red notebook in which were scribbled the verses to the first song he wanted to record that night. It was “Tangled Up in Blue,” which would become one of his most popular songs and a staple of his concert sets for the next three decades.

As before, Bob sat down and taught Weber the song, and after figuring out the capo position that he wanted to use on the twelve-string to create some higher sounds against the lower tones of Dylan’s six-string guitar, Weber taught the other players the song. Dylan scrawled a few chords in the margin of a newspaper, tore it off, and handed this most skeletal of charts to Inhofer, saying, “Here’s the chords to the next song.” Then, while Paul Martinson and the musicians familiarized themselves with the song in readiness for a take, he tinkered with the lyric, refining it until the last moment.

Indeed, even long after the song had passed into the pantheon of rock classics, Dylan continued to play with it, changing a phrase here or a date there, altering characters’ occupations and aspects, and generally exulting in the fluidity of the song’s ever-shifting time scale and locations.

At the New York sessions three months before, Dylan had recorded “Tangled Up in Blue” in the key of E, with an open-tuning configuration. In Minneapolis, he made a conscious decision to literally raise the pitch, kicking off the song in the key of G. But something was still missing from this arrangement. The song was just lying there tamely, not nearly as animated as the lyric demanded. After they played it through, he turned to Kevin Odegard, who sat next to him, tuning his guitar.

“How is it?” he asked. “What do you think?”

Before he could stop himself, Odegard found himself giving the kind of candid judgment that a star of Dylan’s magnitude had probably not heard for the best part of a decade.

“It’s passable,” he heard himself saying, almost before realizing what was happening. Here he was, telling the world’s greatest living songwriter that his latest song was, in effect, pretty mediocre! What was he thinking of? He had let his guard down and thrown a curve ball at Bob Dylan, as relaxed as if he was among friends.

“Passable?” repeated Dylan, twisting his head slightly and giving Odegard that look he gives Donovan in Don’t Look Back, that expression of mild incredulity that can shrivel an ego at fifty paces. Well, that’s it, thought Odegard to himself, as his face turned beet red and the sweat coursed from his pores. I’m finished! I might as well go back to my job on the railroad and tell my grandchildren about the day that Dylan retired my number …

Frantically, Odegard sought to salvage the situation.

“Yeah, it’s good,” he added quickly, amending his opinion, “but I think it would be better, livelier, if we moved it up to A with capos. It would kick ass up a notch. ”

Amazingly, his explanation seemed not only to placate Dylan, but to intrigue him, too. Bob twisted his head, looked around, then down at the floor, musing over the guitarist’s suggestion. Finally, he reached a decision, screwing his shoe on the carpet as if extinguishing an invisible cigarette.

“All right,” he said, nodding. “Let’s try it. ”

Weber and Odegard quickly moved their capos up two frets to effect the key change. Dylan merely adjusted his fingered bar-chord positions, displaying the same skills in transposition that had amazed Richard Crooks and Charlie Brown in New York three months earlier. No capo for Bob, thanks. They got halfway through the run-through before Bob stopped, giving Paul Martinson his “Is it rolling, Bob?” look. The key change had pushed the song up into the higher reaches of Dylan’s vocal range, and the enforced change in his delivery brought a new intensity to the song, which suddenly seemed more urgent and more intriguing; the location jump-cuts between verses, flying past with real cinematic slickness, whisking the listener from one scenario to another with no uncomfortable grinding of verbal gears.

“It gave the song more urgency, and Bob started reaching for the notes,” Odegard later told Rolling Stone magazine.

“It was like watching Charlie Chaplin as a ballet dancer.’

Emboldened by the success of his first idea, Odegard added another, a lick he’d been noodling with since he’d heard something similar on a Joy of Cooking song called ” Midnight Blues. ”

“It was a ‘ring-a-ding-ding’ figure that seemed to work well as an intro and a repeating figure on the front of each verse, so I stuck with it” explains Odegard. Weber’s twelve-string adds body and romance to the arrangement, which is whipped along with peerless grace by the rhythm section: Bill Berg’s delicate but sprightly snare and hi-hat work here is quite extraordinary, a true will-o’-the-wisp spirit at the heart of the song, and Billy Peterson has a ball embellishing the instrumental breaks with melodic bass figures that he would later regard as among his finest recorded work.

“I used a lot of suspensions, and I’m playing some melodic stuff that Paul Martinson brought up in the live take,” says Peterson. “Even now, I look back and I don’t know what I’d do differently now on that one; it’s fine. The urgency of that suspension and release during the verses was more of a jazzy lyrical approach that Berg and I took. I stayed on the A when the band moved down to G, which was uncharacteristic of Dylan. You can hear us digging in. I got into that first take—I knew that was the one. Berg is popping on it.”

Dylan was clearly excited by the revitalized song and delivered a stunning, mesmerizing performance on the first full take—moving and pitching at the microphone like a boxer evading his opponent’s shots, dipping and rolling into his harmonica solo with the eloquent grace of a dragonfly. It was an unforgettable moment for the musicians.

Like so many others in ’60s stereoland, they were enraptured by the voice of as generation, and now here they were in a small room in South Minneapolis, surrounded by fellow dreamers, watching Dylan sing live into their headphones. And not just singing anything but a song that all recognized was a classic, a future standard, something that would become a vital part of millions of lives. And they were right here at the eye of this cultural hurricane, a hurriedly thrown-together backing band, struggling to follow Dylan’s dangerous, thrilling performance— and doing a pretty damn good job of it, too. They realized they would probably never record together again, and certainly not with Dylan; this was a once-in-a-lifetime ensemble that Paul Nelson of Rolling Stone magazine would later describe as “that wonderful pseudonymous band from Minnesota, who clearly have an affinity for Dylan and his music.”

Blood on the Tracks and A Simple Twist of Fate: Bob Dylan and the Making of Blood on the Tracks are available from Amazon.com.

Prices in Canada from Amazon.ca may be lower Blood On The Tracks and A Simple Twist of Fate: Bob Dylan and the Making of Blood on the Tracks.

Blood On the Tracks – Bob Dylan

The quotation from A Simple Twist of Fate is copyright DeCapo Press allowed use as Fair Dealing under the Canada Copyright Act, Section ” In the United States, use of the copyright is Fair Use under Section 107 of the US Code.

By Stephen Pate, NJN Network

Be the first to comment