This article was last updated on April 16, 2022

Canada: ![]() Oye! Times readers Get FREE $30 to spend on Amazon, Walmart…

Oye! Times readers Get FREE $30 to spend on Amazon, Walmart…

USA: ![]() Oye! Times readers Get FREE $30 to spend on Amazon, Walmart…A recent paper by Sue Rahr, a former King County, Washington Sheriff, and Dr. Stephen Rice, Associate Professor of Criminal Justice at Seattle University, looks at how America's police culture has drifted away from a mantra of guardianship to a mantra of warriorship, a change that took place over the decades from the 1960s to the present. Here's a quote from the paper:

Oye! Times readers Get FREE $30 to spend on Amazon, Walmart…A recent paper by Sue Rahr, a former King County, Washington Sheriff, and Dr. Stephen Rice, Associate Professor of Criminal Justice at Seattle University, looks at how America's police culture has drifted away from a mantra of guardianship to a mantra of warriorship, a change that took place over the decades from the 1960s to the present. Here's a quote from the paper:

"As a profession, we have veered away from Sir Robert Peel’s ideal, “the police are the people, and the people are the police,” toward a culture and mindset more like warriors at war with the people we are sworn to protect and serve. As a nation, we have tended to relinquish some of our sacred constitutional rights in favor of the perception of improved safety and security. Constitutional rights are now viewed by some, including some police, as an impediment to the public safety mission. Sadly, many have forgotten that protecting constitutional rights is the mission of police in a democracy."

The authors go on to note that American law enforcement has drifted off course; building a safe distance from community members by using equipment, technology and pain compliance to deal with the public rather than building close ties with a community. Police that have developed a trust-based relationship (i.e. as a guardian) with their community are far more likely to be effective at their jobs, unlike police who operate with a warrior mentality.

Let's look at one of the main reasons why this change has taken place.

The seeds of the "us against them" warrior mentality are planted during the training of police recruits. Police academies are usually modelled after military boot camps where recruits are expected to follow orders and rules passed down from his or her superiors without question. The recruits have no power and are often verbally and physically punished for violating rules. This model of training has little to do with the realities of policing and establishes a mindset of both verbal and physical violence that is taken to the job. Rather than training recruits using the boot camp model, police need to be trained in both critical thinking, decision-making, de-escalation skills and communication. Instead, training of recruits focusses on physical control tactics and weapons, a recipe for disaster when the new recruit hits the streets, particularly since high-risk physical encounters with civilians are relatively rare events.

After graduation, new police are sent into the community with a newly instilled sense of power since they are no longer under the direct control of their police academy supervisors. Even though they are trained to be submissive to their superiors, most police officers working the streets of America have very little direct and consistent supervision; this means that they are operating without being given specific orders and they are making decisions based on a lack of rules since it is impossible to generate and memorize enough rules to cover all situations that police may encounter. In fact, newly trained officers are often placed in the least desirable facets of street policing. In the case of New York City, new officers were placed in some of the city's highest crime rate districts under "Operation Impact". This program was changed in 2014 when Police Commissioner William Bratton altered the program so that rookie officers were teamed with veterans. While the original program did reduce crime, many critics said that it contributed to very widespread use of the "stop, question and frisk" tactic that led to increased tensions between minority residents and the police.

Now, let's look at an example of how police training can change to train better police officers. Police training at the Washington State Criminal Justice Training Commission (WSCJTC) in the state of Washington was modelled on the boot camp premise where a "deterrence strategy was used to maintain discipline and control". Recruits were verbally berated right from the first day of training and were required to salute and remain silent when they encountered a staff member. Violations were met with physical punishments including extra pushups and running of laps. In-class training focussed on physical skills that were accompanied by stories about officers that had been killed while on duty. There were very few classes on communication skills with physical control being emphasized. Training posters reminded recruits of the deadly threats that they would face at the hands of civilians and some training materials included to use of skulls and crossbones as reminders of the potential deadliness of civilians.

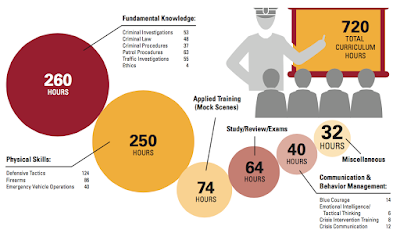

Author Sue Rahr implemented changes to police training at WSCJTC with the goal of changing the mindset of police culture. Here is a graphic showing how 720 curriculum hours of police training is divided by subject matter over a 5 month period:

The first program change that was made eliminated the requirement to salute a staff member, replacing it with a requirement to engage the staff member in conversation, maintaining eye contact and showing respect by calling them "sir" or "ma'am". Fear and humiliation that were traditionally used as motivators were replaced with coaching that promotes a high level of physical fitness. These actions were taken to build a sense of teamwork rather than a sense of fear. The implementation of both behavioural and social science programs into the curriculum contributes to both better officer safety and improved trust levels by the public.

There is no doubt that police need to be trained to protect themselves from low-frequency attacks by civilians. However, although police and soldiers both carry weapons and wear uniforms, the similarity should end there. The rules of engagement should be different for both groups, however, recent media reports of police violence toward those that they are supposed to "serve and protect" would suggest otherwise.

In conclusion, rather than seeing images of American police that look like this:

…we, as generally law-abiding civilians, can only hope that this new model of police training results in police officers that are less interested in confrontation with members of the public and more interested in being a constructive part of our communities.

Click HERE to read more of Glen Asher's columns

You can publish this article on your website as long as you provide a link back to this page.

Be the first to comment