Despite the fact that headline employment data shows what appears to be a healthy economy, millions of work-deprived Americans who have fallen off the Bureau of Labor Statistics radar screen would suggest otherwise. One of the greatest declines in America's "job creation machines" has been in manufacturing. Here is a graph showing what has happened to the number of manufacturing jobs in the United States since 1939:

We have to go all the way back to World War II to find manufacturing job levels that are the same as they are today.

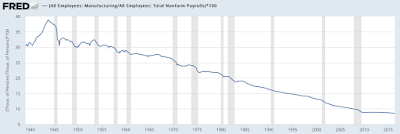

Here is a graph showing the percentage of non-farm employees that are involved in the manufacturing sector:

Right now, only 8.5 percent of non-farm workers in the United States are involved in the manufacturing sector, down from nearly 26 percent in 1970 and 13.2 percent in 2000. Since the Great Recession began, the number of workers in manufacturing has dropped from 13.746 million in December 2007 to its current level of 12.296 million, a loss of 1.45 million jobs. Even worse, since China acceded to the World Trade Organization in December 11, 2001, the United States has lost 3.415 manufacturing jobs.

Here are some additional statistics from the Economic Policy Institute about America's beleaguered manufacturing sector. Between 1998 and 2013, nearly one-third of U.S. manufacturing jobs disappeared along with over 80,000 manufacturing establishments. While manufacturing made up 12.1 percent of GDP in 2014, its footprint in the American economy is far larger; in addition to the 12 million or so workers directly employed in manufacturing, an additional 17.4 million workers are supported indirectly by the manufacturing sector. In other words, manufacturing directly or indirectly supports more than 29.6 million jobs or 21.3 percent of all U.S. employment (2014 data). As well, manufacturing is responsible for $208 billion worth of business research and development or nearly two-thirds of all U.S. business spending on R&D. In addition, when the services that manufacturing businesses purchase are factored into the equation, the value of gross output from this one sector amounted to $6.2 trillion or roughly 35 percent of GDP

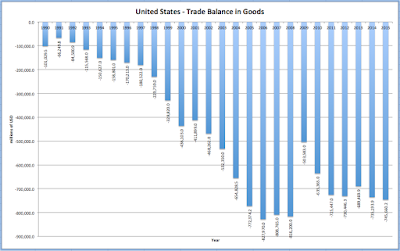

Here is a graphic showing the current United States goods trade balance, a relatively accurate proxy for the manufacturing trade balance since manufacturing constituted 86.9 percent of total U.S. trade in goods and 94.3 percent of total trade in non-oil goods (2015 data):

Note the rather dramatic increase in the goods trade deficit after the much-touted (by Bill Clinton, no less) WTO trade deal with China. In May 2016, exports of goods were $119.8 billion and imports of goods was $182.1 billion, resulting in a goods trade deficit of $62.3 billion, slightly larger than the goods trade deficit for all of 1991!

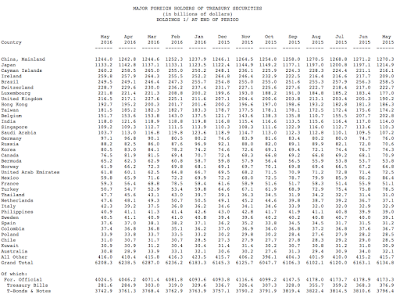

It's pretty obvious that the manufacturing sector was and still could be a significant job creator for the United States economy, however, there is one key factor that has interfered with this mechanism. In a Policy Memo by Robert Scott at the Economic Policy Institute, the author outlines the root causes of the problem. Globalization has created an extremely competitive trade environment and all nations, particularly those in Asia, are looking for an edge to give them increased market shares. Through the use of currency manipulation, these nations have affected the value of their currencies to make their domestically produced goods less expensive and, by comparison, American-made goods more expensive. In this case, currency manipulation acts like a form of tax or tariff on imported goods, making domestically produced goods look more attractive to local consumers and exported goods more attractive to outside consumers. Nations that run large and consistent trade surpluses with the United States (i.e. the United States runs trade deficits with these nations) tend to be currency manipulators. Governments can manipulate currencies by buying foreign assets denominated in the currencies of other nations (i.e. U.S. Treasuries) which increases the demand for that currency relative to their own currency. China and roughly 20 other Asian nations have purchased trillions of dollars worth of U.S.-denominated assets over the past 15 years (again since China joined the WTO in 2000) and this has resulted in this:

To give you a sense of how big the problem has become, back in 2000, China held only $60.3 billion in U.S. Treasuries and Japan held $317.7 billion. By 2005, four short years after China joined the WTO, their holdings of Treasuries had grown to $310 billion, five times what they held in 2000. Can anyone say "currency manipulation"?

While Donald Trump is correct in announcing that China's currency manipulation is responsible for the massive trade deficit, his claims that countervailing duties will clean up the problem with trade deficits will not really help American workers. Increasing tariffs on imported goods will achieve only one thing; raising the cost of goods that the United States imports. Any new job creation in competing industries would be limited because of the negative effect of tariffs on domestic prices. The biggest part of the problem for American workers is the excessive demand for the United States dollar which has been driven up to excessively high values; in the past two years alone private capital flows in China and Europe have driven the dollar up by an additional 15 percent. This will have a medium- and long-term negative impact on U.S. trade deficits and the creation of domestic manufacturing jobs. How can we tell when the dollar is fairly valued? The author of the memo suggests that the dollar will be fairly valued when the United States experiences neither a trade surplus nor a trade deficit. This balance would be accomplished when the U.S. dollar falls by between 25 and 30 percent on average and by more when measured against the currencies of China, Germany and Japan, for instance, the value of the dollar would have to fall by 37 percent against China's yuan renminbi and 50 percent against Japan's yen. If trade balance were achieved, there would be a significant increase in the demand for United States-manufactured goods which would ultimately result in the rebuilding of the lost manufacturing sector jobs.

How can an end to currency manipulation be achieved? Economists have have suggested two methods that the United States could use:

1.) intervene in the currency market by engaging in countervailing currency intervention (CCI) by purchasing large amounts of foreign assets denominated in the currencies of the trade surplus nations.

2.) impose an adjustable market access charge which would act as a tax or fee on all capital inflows. This would result in a decrease in the demand for dollar-denominated assets and would push down the value of the U.S. dollar.

To keep these policies free of "political meddling", the author suggests that the two approaches could be implemented by the Department of the Treasury (or less appealingly, at least to me, by the Federal Reserve). This would remove the ability of the president or Congress to interfere with the neutrality of the system.

While imposing countervailing duties or tariffs on nations that are taking part in currency manipulation seems like a great idea, it will do little to solve the problem of increasing demand for American exports. The whole point of realigning the value of the U.S. dollar is two-pronged; it makes imported goods more expensive to American consumers and, most importantly, it makes American goods more competitively priced to foreign consumers. It is that effect of reducing currency manipulation that will result in the resurrection of American manufacturing sector and putting millions of workers back into well-paying jobs. Even a million new manufacturing jobs would help.

Click HERE to read more of Glen Asher's columns

You can publish this article on your website as long as you provide a link back to this page.

Be the first to comment