A graphic-novel adaptation of Mohamed Choukri’s iconic For Bread Alone — by Moroccan comics artist Abdelaziz Mouride (1949-2013) is finally coming to print:

By Olivia Snaije

It took the tenacity of an independent comics book publisher based in Marseille to track down and publish an unfinished adaptation in French of Mohamed Choukri’s Le Pain Nu (Al-khubz al-hafi), or For Bread Alone by one of Morocco’s best-known comics artists, Abdelaziz Mouride.

Mouride, who died in 2013, had nearly finished his version of For Bread Alone, but hadn’t yet found a publisher. Some of the strips were still in black and white, others in the finished watercolor version. Simona Gabrieli, a linguist and co-founder of Alifbata, which publishes comics translated from Arabic, had been thinking about starting a collection of Arab classics in comic book form, pairing the adaptation with a comics artist from the country where the author was from.

As someone who has worked on multicultural educational projects and is interested in building bridges across the Mediterranean, she says she likes the idea of transforming classical literature into a medium that is more accessible. As magical encounters sometimes happen, at a comics fair in Paris, Jean-François Chanson who used to run the French comics book publisher in Morocco called éditions Alberti, introduced himself to her and told her about Mouride’s version of For Bread Alone.

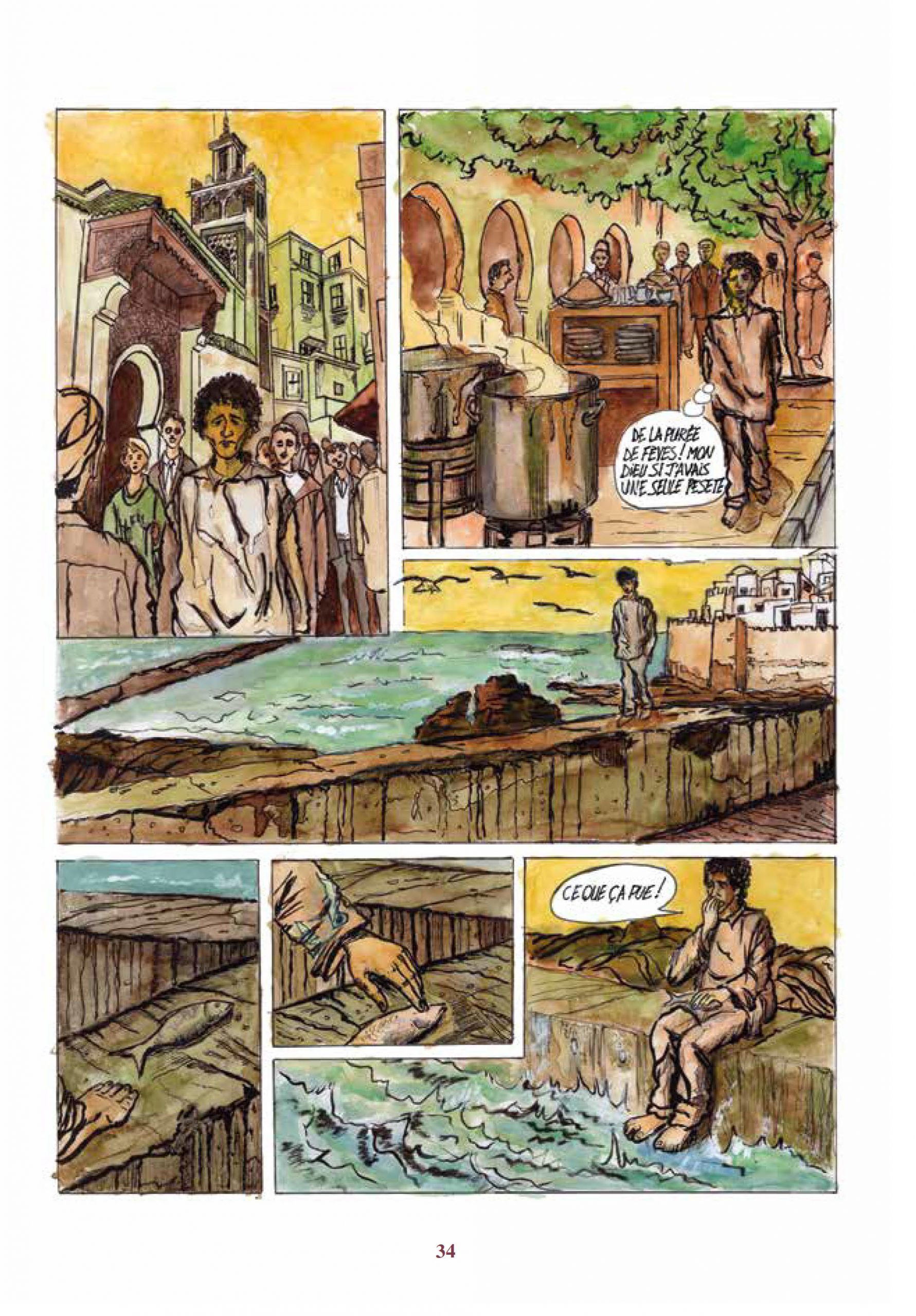

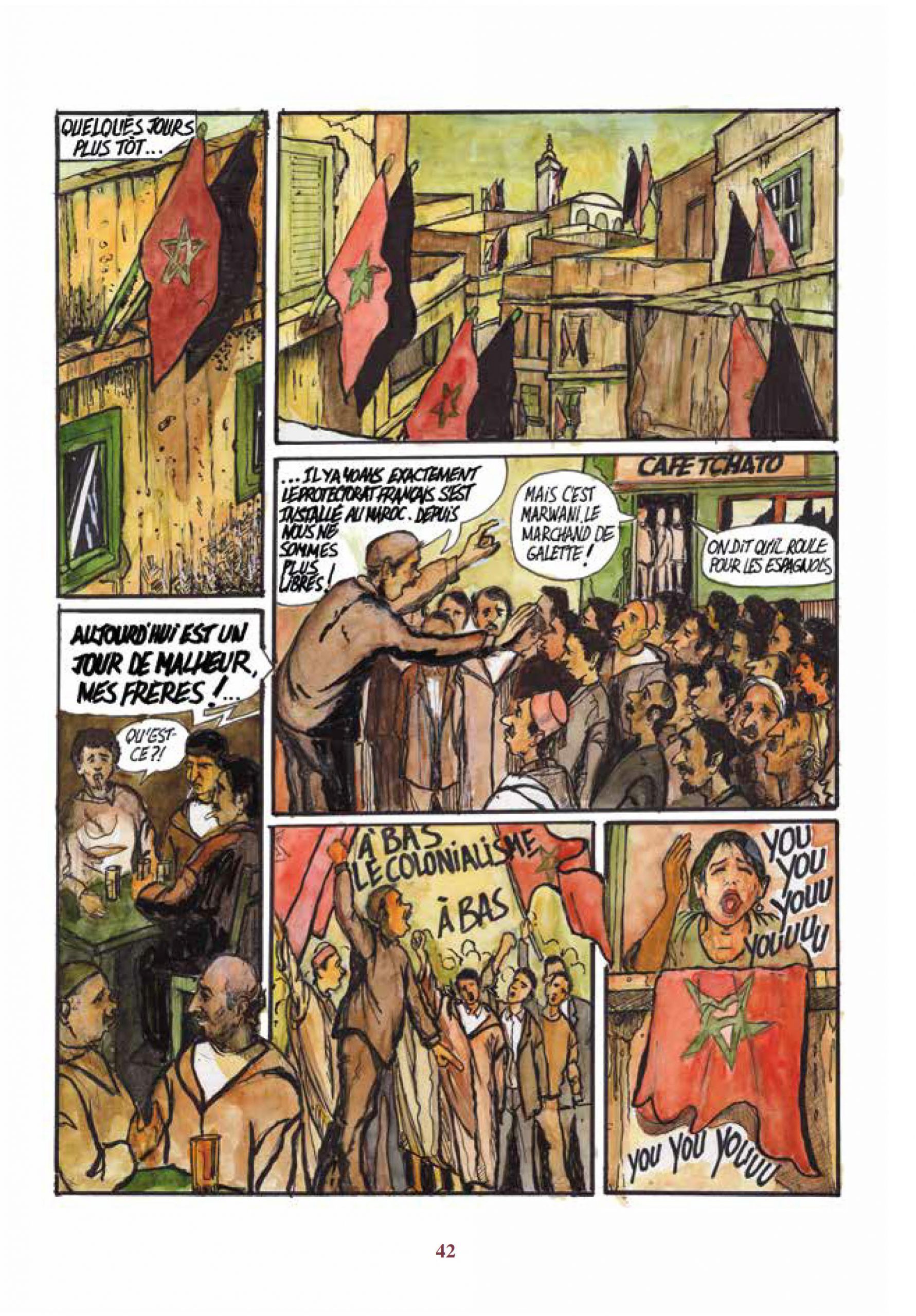

As a quick reminder, Choukri’s slim autobiographical book, El-Khubz el-hafi, written in Arabic, was first published in English in 1974 as For Bread Alone, translated by Paul Bowles. It was published in French as Le Pain Nu in 1980, translated by Tahar Ben Jelloun. It wasn’t published in Arabic until 1982 and it was immediately banned in Morocco and other Arab countries. Moroccans had to wait until 2000 to read Choukri’s book. For Bread Alone recounts Choukri’s childhood in the Rif, plagued by famine and an alcoholic and violent father. At eleven, he becomes a street child in Tangiers and discovers drugs, alcohol, and sex. Caught up in independence riots, he is imprisoned briefly at age 20, where a fellow inmate encourages him to learn to read and write, sparking a love for literature that pushed him to study Arabic and begin to write.

Back in Paris, Gabrieli said she was very moved by the information about the comic book adaptation. Choukri’s book was the first that she had ever read by an Arab author, and the first Arab comic book she ever read was by Abdelaziz Mourid, when she unearthed at the iconic Librairie des Colonnes in Tangiers, his On affame bien les rats! (They starve rats, don’t they?), a revised version of an earlier work he had written while imprisoned under King Hassan II’s régime. Chanson put her in touch with Mouride’s publisher, Miloudi Nouiga, who had the manuscript, and the author’s son,Jad. Choukri had given Mouride permission to adapt his novel, but the permission was oral, and not a written contract. Gabrieli set off on what she describes as a “publishing adventure” via Choukri’s former literary agent, Roberto de Hollanda, and other leads, which ended up taking a year and a half in order to find the rights holder. The answer lay with the Madrid-based publisher Miguel Lázaro of Cabaret Voltaire, who, besides Choukri, publishes Abdellah Taia, Leila Slimani, Rachid Boujedra, and Tahar Ben Jelloun.

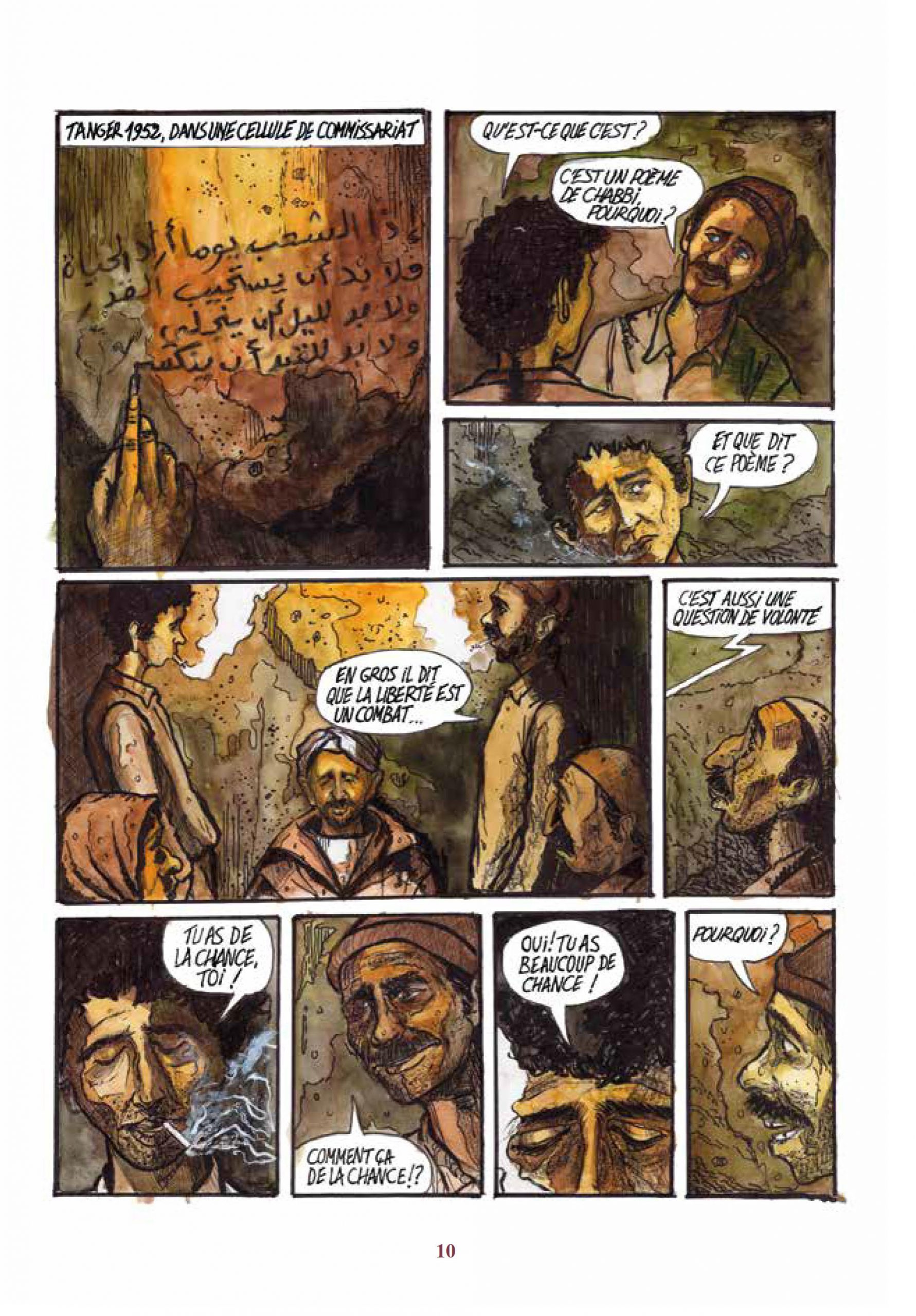

Mouride began his adaptation of For Bread Alone with the scene in which Choukri is detained in a police station and decides he wants to learn to read and write after meeting a fellow prisoner. He tells his cellmates about his childhood and teenage years in the form of flashbacks. At times Mouride used Tahar Ben Jelloun’s French translation word for word, and at other times he rewrote the dialogues.

It is fitting that Mouride began his comic with a detention scene—he discovered Choukri’s book while he was in prison. Thanks to a wonderfully informative afterword written by Jean-François Chanson with the input of Mouride’s son, Jad, the reader is given a real sense of who Mouride was.

Abdelaziz Mouride was born in Casablanca in 1949. In 1969 he co-founded a secret left-wing political cell called the March 23rd Movement named after the deadly repression Hassan II’s government inflicted on student demonstrators on March 23rd, 1965. In 1974 he was arrested and tortured, and in 1977 following his trial, was given 22 years in prison. Held for a time in the infamous Kenitra prison where he stayed until 1984, he undertook an extremely risky endeavor, which was to draw in comic strip form, his and his prison mates’ incarceration and its abysmal conditions: torture, isolation, death, sadistic guards, hunger strikes and attempts to force feed prisoners. The strips were smuggled out of Morocco by Amnesty International and translated into French by the poet and former detainee, Abdellatif Laâbi and published in Belgium under a pseudonym in 1982 as Dans les entrailles de mon pays (In the bowels of my country).

It was in Kenitra that Mouride discovered the French version of For For Bread Alone; although at the time it was banned in Morocco, Amnesty International distributed it along with other books to prisoners. In it, he said, he saw a “parable of his past, and that of his country.”

As Moroccan publisher and author Kenza Sefrioui writes in her introduction to the comic, “…Moroccan society, deeply inequitable and harsh, regrettably provides abundant material.”

But Mouride saw the uplifting side to Choukri’s work as well. Chanson writes in his afterword that Mouride told a journalist for a Belgian paper in 2010: “The strength of our taboos mean that we tend to hide the problems we have related to poverty; such as prostitution or street children. [But] what struck me the most in this book is not the dissolute life of young Choukri, but the fact that a boy who spent his life in the street amidst prostitution and alcohol, was reborn at age twenty from its ashes.”

Mouride, like Gabrieli, had felt that comics reach all layers of the population. In this potent and beautiful publication one is not only reminded of the importance of Choukri’s text, but also of the powerful and creative work of an artist who lived through Morocco’s “years of lead” and survived unspeakable years in detention.

You can buy the book directly from the Alifbata site, here; the publisher will have the book up beginning next week. If you happen to be in Paris for Maghreb Orient des Livres, set to take place the weekend of February 7, Alifbata will have a stand there as well. If you are planning on being in the south of France, an exhibition of Abdelaziz Mouride’s work on For Bread Alone will be exhibited at the Jean Giono center in Manosque, from February 10-March 7, 2020; the book will also be on sale at the exhibit.

For those who need another For Bread Alone fix, Algerian director Rachid Benhadj was able to convince Mohamed Choukri before his death to give him the film rights, and even to agree to a cameo role. Filmed in Rabat and Tangiers with the actor Saïd Taghmaoui incarnating Choukri as an adult, the 2005 film can be viewed here.

Olivia Snaije is a Paris-based journalist and editor. She has written several books on Paris, co-edited the photography book Keep Your Eye on the Wall: Palestinian Landscapes, and translated Lamia Ziadé’s Bye Bye Babylon.

Click HERE to read more from this author.

You can publish this article on your website as long as you provide a link back to this page.

Be the first to comment