There is more than one reason why Russia is interested in Crimea and the Ukraine. One of the reasons is likely related to the potential for oil and natural gas reserves on and adjacent to the Crimean Peninsula and onshore in both Eastern and Western Ukraine, a topic that received little attention from the world's media until the geopolitical situation in Ukraine started to heat up.

Back in the Soviet days, the oil industry discovered indications of hydrocarbons, however, productivity was poor. Flow rates were low and were considered subeconomic given that the porosity in the fractured reservoirs was low. With recent advances in production techniques, the potential to produce hydrocarbons from these tight reservoirs has increased substantially, particularly with the use of fracking to produce natural gas and condensate from shale reservoirs.

There are two key areas for potential hydrocarbon accumulations in Ukraine; offshore in the Black Sea around Crimea and onshore in both eastern and western Ukraine.

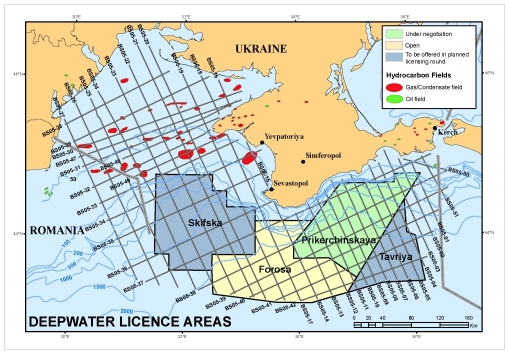

Here is a map showing the key oil and gas exploration and development areas in the Black Sea, noting the Crimean Peninsula in the top right side of the screen capture:

Here is a close up showing the key Ukrainian offshore exploration licences:

Just prior to the collapse of the Yanukovych government, Ukraine was very close to signing a $735 million production-sharing agreement with ExxonMobil and Royal Dutch Shell. The deal would have seen two wells drilled off the southwest coast of Crimea in the Skifska area. The operators were optimistic that even though no drilling had taken place in this block, a recent natural gas discovery in the Romanian part of the Black Sea could be a harbinger of economic reserves in the Skifska licence. Going back further, in 2012, the two companies along with Romania's OMV Petrom and Ukraine's state-owned Nadra Ukrainy were picked to spend between $10 and $12 billion to develop the Skifska field which is projected to have reserves of between 7 and 8.8 Tcf and would have produced about 175 Bcf per year over a 50 year production sharing deal, reducing Ukraine's very heavy dependence on imported natural gas from Russia. Not surprisingly, the deal was contested by Russia's Lukoil.

Not surprisingly, ExxonMobil announced in early March 2014 that further activity on its Skifska licence were on hold until the political situation in Ukraine was resolved.

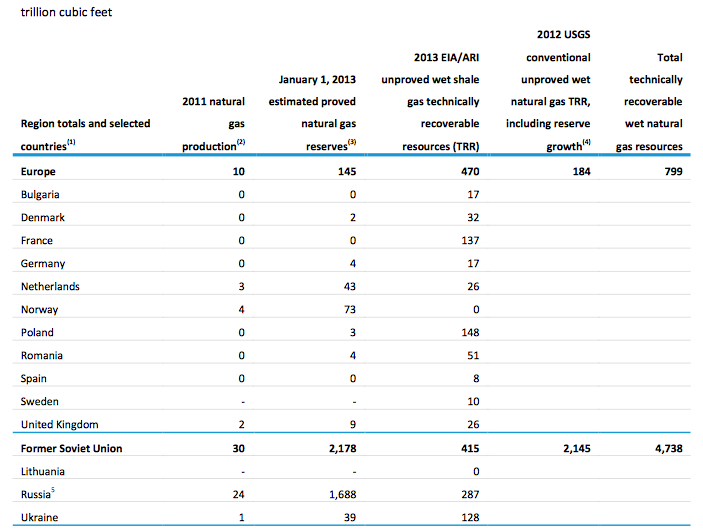

Now, let's look at the onshore hydrocarbon resource potential. According to the United States Energy Information Administration, Ukraine has Europe's third largest unproved, technically recoverable shale gas reserves after Poland and France as shown on this chart:

Shale gas in Ukraine is located in two main areas; Yuzivska located in Eastern Ukraine and Olesska located in Western Ukraine. According to EIA's 2013 shale gas report, Ukraine has 128 Tcf of natural gas and 0.2 billion barrels of oil in its shale gas fields located in the black shales of the Deniepr – Donets Basin in Eastern Ukraine, the basin which accounts for most of Ukraine's onshore petroleum reserves and the organic rich shales of the Carpathian Foreland Basin in Western Ukraine as shown on this map:

Here is a closeup of the Dnieper – Donets Basin showing the areas in Ukraine that are prospective for oil, wet gas or condensate and dry gas:

Ukraine State Service of Geology and Mineral Resources announced that shale gas reserves in the country totalled 247 Tcf. If this were the case, Ukraine alone would have just over half of the total shale gas reserves among all European nations that were not formerly part of the Soviet bloc.

In May 2012, Ukraine picked Shell and Chevron Corp. to explore and develop two potential onshore shale gas fields in Western and Eastern Ukraine.

In Western Ukraine, Chevron will initially invest $350 million annually with a total investment of around $10 billion. A 50 year production sharing agreement was signed in November 2013. The Olesska (or Oleskaya) shale reserves, located in western Ukraine, are estimated to be roughly 53 Tcf according to the Ukraine government and could produce up to 350 Bcf annually. The field is located along strike with Poland's Lublin Basin where Chevron already has shale licences. Here is a map showing the location of the Lublin Basin and where it borders with Ukraine:

Here is a map from Chevron showing their areas of interest in Ukraine, Poland and Romania:

In mid-January 2014, Chevron announced that it would start producing gas by the end of 2014.

Ukraine also signed a contract with Royal Dutch Shell to explore shale gas potential on the Yuzivska block in Eastern Ukraine. This area is estimated to have between 71 and 107 Tcf of shale gas and Shell has made an initial spending commitment of $200 million in the first stage of exploration and an anticipated minimum of $10 billion (and up to $50 billion) over the 50 year life of the agreement. Shell expects to start production from the Yuzivska block in 2015.

Interestingly, in June 2013, Ukraine's Prime Minister Mykola Azarov claimed that Ukraine would be natural gas self-sufficient within 10 years and that it would be able to export some gas as well by the mid-2020s. With Ukraine currently getting over two-thirds of its natural gas from Russia and being Russia's second largest natural gas customer, one has to wonder how much of a role recent oil industry activity in Ukraine and Crimea, in particular, have played in Russia's current political moves in the area. With major international oil companies about to break Russia's near monopoly on natural gas in Ukraine, would one have to think that Russia and Gazprom would feel somewhat threatened. When one looks at how many deals Ukraine has signed with multinational oil companies in the past two years, the timing of Russia's return to the Ukraine seems more than coincidental.

Click HERE to read more of Glen Asher's columns

You can publish this article on your website as long as you provide a link back to this page.

pretty much emily i awesome