The central bankers' central bank, the Bank for International Settlements or BIS, recently released its annual report on the worlds economy. In this posting, I want to take a look at a few of the more interesting (and rather frightening) comments made by the authors in this year's edition.

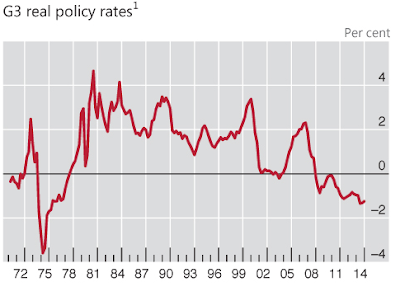

The authors open the report with a chapter entitled "Is the unthinkable becoming routine?". As shown on this graphic, real interest rates for Japan, the United States and Germany have never been this low for this long:

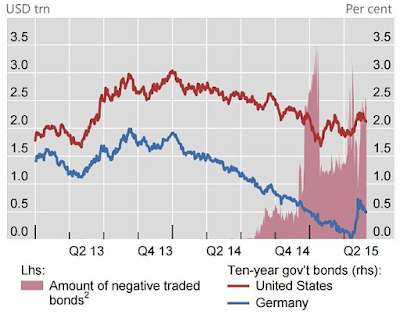

This has had a significant impact on bond rates; between December 2014 and the end of May 2015, on average, approximately $2 trillion in global long-term sovereign debt (particularly euro debt) was trading with negative yields as shown on this graphic:

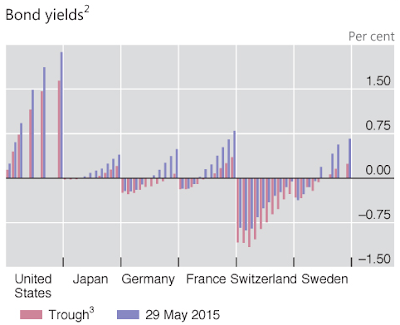

Here is another graphic showing how widespread negative yields had become in the first half of 2015:

While that situation has corrected itself to some degree, at their trough, the yields on French, German and Swiss sovereign bonds were negative out to five, nine and fifteen years respectively.

These ultra-low rates are evidence of a broad malaise in the global economy. The authors note that debt levels and financial risks are still exceedingly high despite the fact that we are 6 full years into the "recovery" and that the world's leading central banks have used the aforementioned extraordinary tactic of using near-zero interest rates and other non-conventional monetary policies to prop up the global economy which is growing, but at unbalanced rates.

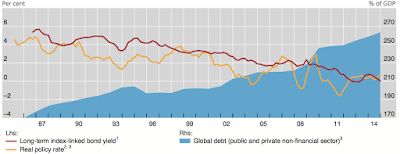

The authors note that the current very low interest rates that have prevailed for such a lengthy period of time are not "equilibrium rates" that are conducive to sustainable global expansion, rather, the have contributed to the current global economic weakness by fuelling financial booms and busts. The result is too much debt, too little growth and low interest rates that "beget lower rates". This is quite apparent in this graphic that shows what has happened to the global public and private non-financial sector debt levels as a percentage of GDP as shown on this graphic:

One point of concern is the credit that has been given to non-banks in emerging market economies. Since early 2009, the level of this credit has almost doubled to more than $3 trillion. Countries that export commodities are particularly at risk, including those in Latin America. At the end of 2014, China was the world's eighth largest borrower in terms of cross-border bank claims, reaching $1 trillion or double the amount just two years prior.

Ultra-low interest rates have an impact on the private economy; low rates reduce banks' interest rate margins and undermine the profitability of both pension plans and insurance companies. Our current pervasive low rates have also resulted in severe misplacing in both equities and corporate debt markets (i.e. they create asset bubbles). Low rates can also create problems for the broader economy; pension funding is less secure now than it has been in generations, increasing the need for individuals to save more for retirement which can weaken consumer demand.

Let's close with this excerpt from the report:

"The resulting picture is that of a world that has been returning to stronger growth but where medium-term tensions persist. The wounds left by the crisis and subsequent recession are healing, because balance sheets are being repaired and some deleveraging has taken place. Recently, the strong and unexpected boost from energy prices has helped too. In the meantime, monetary policy has done its utmost to support near-term demand. But the policy mix has relied too much on measures that, directly or indirectly, have entrenched dependence on the very debt-fuelled growth model that lay at the root of the crisis. These tensions manifest themselves most visibly in the failure of global debt burdens to adjust, the continued decline in productivity growth and, above all, the progressive loss of policy room for manoeuvre, both fiscal and monetary…Room for manoeuvre in macroeconomic policy has been narrowing with every passing year. In some jurisdictions, monetary policy is already testing its outer limits, to the point of stretching the boundaries of the unthinkable. In others, policy rates are still coming down. Fiscal policy, after the post-crisis expansion, has been throttled back, as sustainability concerns have mounted. And fiscal positions are deteriorating in EMEs where growth is slowing."

It is becoming increasingly apparent that the current environment of ultra-low interest rates have left the world's central bankers ill-equipped to fight the next economic crisis. The long-term monetary experiment has left central bankers with little room to manoeuvre because, as the Federal Reserve is discovering, they have backed themselves into a very uncomfortable corner from which extrication will likely be extremely painful.

Click HERE to read more of Glen Asher's columns

You can publish this article on your website as long as you provide a link back to this page.

Be the first to comment