Iraq holds great significance for Iranian Shiites as a center of religious learning, and has a Shiite-majority population. Under the regime of Saddam Hussein, however, Iraq tried to bury the Ayatollah Khomeini’s Islamic Revolution by launching a catastrophic war against Iran in which almost 300,000 Iranians and almost 200,000 Iraqis died, and more than one-million people were injured. In his 2002 State of the Union speech, U.S. President George W. Bush lumped Iraq and Iran together as members of an axis of rogue states, causing Iran to fear that U.S. designs for regime change in the Middle East would extend beyond its overthrow of Saddam in 2003. Following the U.S. withdrawal from Iraq in 2011, Iran became Baghdad’s most influential neighbor.

Iraq holds great significance for Iranian Shiites as a center of religious learning, and has a Shiite-majority population. Under the regime of Saddam Hussein, however, Iraq tried to bury the Ayatollah Khomeini’s Islamic Revolution by launching a catastrophic war against Iran in which almost 300,000 Iranians and almost 200,000 Iraqis died, and more than one-million people were injured. In his 2002 State of the Union speech, U.S. President George W. Bush lumped Iraq and Iran together as members of an axis of rogue states, causing Iran to fear that U.S. designs for regime change in the Middle East would extend beyond its overthrow of Saddam in 2003. Following the U.S. withdrawal from Iraq in 2011, Iran became Baghdad’s most influential neighbor.

Unequal Nationalisms

In the late 1970s relations between Iran and Iraq were unequal and tense, and the two countries held very different global allegiances. Iraq was in great conflict with the Shah’s Iran, says Paul Salem of the Middle East Institute, because the Shah was a close ally of the United States, whereas Iraq had moved toward the Soviet camp during the Cold War. The Shah promoted a nationalist, Persian identity while Iraq was in the grip of strong Arab nationalism in the form of Baathism. Both envisioned themselves as regional hegemons, although Iraq had a narrower outlet onto the Persian Gulf, which was itself cause for dispute.

“While they were rivals,” says David Crist, a U.S. government historian with a military background, and author of The Twilight War, “Iran was always so much stronger, and Iraq so much weaker, that Iran dictated what was going to go on, much as they did in a lot of other areas in the Gulf.” Iran, he says, was able impose the 1975 Treaty of Algiers on Iraq, which defined the two countries’ Shatt al-Arab boundary dispute in a manner advantageous to Tehran. The Algiers settlement also ended each country’s support for rebellious minorities on the other’s territory—Iran for Kurds in northern Iraq, and Iraq for Arabs in Khuzestan.

Revolution as Opportunity

While the Algiers accord stabilized the countries’ ties for a time, Ruhollah Khomeini announced in June 1979 that Iran would no longer be bound by it, and Saddam declared it void the following year on the grounds that Iran had not implemented all provisions. For Saddam, Salem says, the revolution presented both a threat and an opportunity.

Saddam was feeling very powerful at that time, Salem says. “This was during the oil boom. Iraq had massive resources, and at that moment, Iran sort of crumbled.” He sought to seize historically Arabic-speaking Khuzestan Province. He won support from Sunni Arab states in the Persian Gulf, as well as more qualified backing from the Soviet Union, which was his historic ally, and from the United States. “He thought, though he turned out to be mistaken, that this time of revolution would be a time when Iran would be weak,” Salem says. “As we know, Iran and Iraq ended up in a war that drained them both.”

On the other hand, the character of the Iranian Revolution unnerved Saddam. “There was very aggressive rhetoric, that they had defeated the Americans and their Shah, and that the next step would be to export the revolution across their borders, certainly to the Arab world, certainly to the Islamic world,” Salem says. “There was a sense from Iraq, with backing from the Gulf States, to pre-empt such activity.” Saddam, he says, also feared the prospect of revolutionary sprit emerging among Iraqi Shiites.

Leaders of the Islamic Dawa Party, a strong Iraqi Shia party, had fled to Iran in the 1970s following Saddam’s attempts to suppress them, and Iran pressured them to adopt Khomeini’s understanding of Islamic government. In 1982, the Iranian government sponsored the creation of the Supreme Council for the Islamic Revolution in Iraq (SCIRI) to provide an umbrella organization for Iraqi Shiite groups, including Dawa. The SCIRI was founded by Ayatollah Mohammad Baqir Al-Hakim, a Najaf-born cleric who had been tortured by Saddam’s agents in 1972, and had fled to Iran in 1980.

The Iraqi regime was suspicious and paranoid about clerical activity in the Shia shrine cities of Najaf and Karabala, says Ahab Bdaiwi, lecturer and researcher in Middle Eastern and Islamic history at the University of St. Andrews. In 1920 clerical leaders in Najaf had galvanized the masses to take up arms against the British and were celebrated as national heroes. But under Saddam’s rule, he says, there was a widespread perception among clerics that Saddam’s forces had infiltrated the seminaries. “Whatever pro-Iran sentiments they may have had were not visible in public,” he says. “Many simply retired from politics.”

Yet there were notable exceptions, Bdaiwi says, such as Mohammad Baqir al-Sadr, (father-in-law of Muqtada al-Sadr) who was a vocal critic of Saddam’s regime and issued a ruling forbidding Iraqis from joining the Baath party. “When the revolution happened, he pledged allegiance, or semi-allegiance, to Khomeini, whereby he said, ‘Khomeini’s revolution has realized everything I have theorized about Islamic government.’ Of course, he was eventually executed.” Saddam’s move to war, Salem says, was in part an attempt to pre-empt what he saw as the prospect of religious subversion. “He was able to hold the Iraqi army together,” he says. “Much of the army was Shiite, and they did fight against the Iranians.”

Iranian soldiers capture an Iraqi tank during the Iran-Iraq War

Post-War Cold War

Following the end of the Iran-Iraq War, the two countries maintained minimal, if hostile, relations. When the United Nations-brokered ceasefire went into effect in August 1988, both sides exchanged prisoners, although both sides made accusations that the exchange had not been complete. “There was no diplomatic exchange. The Iraqi government severely limited the flow of Iranian pilgrims to Karbala [and Najaf]. There was occasional cross-border fire. The Mujahedin-e-Khalq (MEK) was active along the border, and did a few raids into Iran.” It was, in Crist’s words, almost a state of cold war.

The MEK presence in Iraq was a source of considerable friction between the two countries. “The Iranians to this day still consider them a terrorist organization and blame them for a tremendous number of attacks on IRGC [Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps] officers. For them it was the equivalent of Saddam harboring Al-Qaeda.” Iran, meanwhile, hosted the anti-Saddam Badr Corps, which was composed of Shia defectors from the Iraqi army.

First Gulf War

Then came Iraq’s 1990 invasion of Kuwait, and the U.S.-led international response against it, in which Iran was not involved. “They were exhausted by the Iran-Iraq War,” Crist says. “They were flat in terms of their ability to exert military power, their economy was in a shambles, the population had been decimated. Iran couldn’t have done anything if it had wanted to.” And yet, Salem says, Iran was happy to see Saddam chastened even if it was wary of U.S. presence in the Gulf, and did not want to see him keep Kuwait and expand his power. “He was the mortal enemy. He had tried to kill the revolution in its infancy, and they could never forget that.”

Iran even quietly offered the U.S. support. “There was a deal done with the U.S. through one of the Gulf States,” Crist says, “where we were trying to make sure the Iranians didn’t interfere. The Iranians came back very supportive, and even said, ‘If your pilots get shot down over Iran, we’ll rescue them and return them to you.’” Iran, he says conveniently ignored U.S. planes that strayed into Iranian airspace.

The first Gulf War saw Iraq’s isolation steepen as Iran began to escalate diplomacy in the region. The sanctions regime imposed on Iraq following the war, Salem says, meant that Iraq became a prisoner, not a player. “Iran was somewhat isolated, but in the 1990s, President Rafsanjani, and then President Khatami, reached out to the Arab countries in the Gulf and moderated Iran’s position, while Iraq was simply in quarantine.”

The 2003 Iraq War

The 2003 U.S. invasion of Iraq overthrew Iran’s long-time enemy, but Iran’s leaders speculated fearfully about U.S. intentions. “From the Iranians’ perspective,” Crist says, “everything the United States does is secretly directed at them.” Iran, he says, feared that the U.S. might use Iraq as a base from which to effect regime change, a fear exacerbated by Bush administration rhetoric. The U.S. and Iran had been in private negotiations since before the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan, and in 2002, Iran sought to discuss coordination with regard to the U.S. invasion of Iraq, and even offered to allow the Badr Corps to work with U.S. forces. “They wanted to really haggle. If the U.S. was bound and determined to invade Iraq, they wanted to have some control over the post-war environment.”

The U.S., he says, rejected Iran’s approach, but upon invasion of Iraq passed a demarche to Iran to reassure it that the U.S. had no military intentions toward Iran, and to advise it stay out of the conflict. Again Iran agreed to pick up downed U.S. pilots, and viewed the American invasion as a historic opportunity. “As we go up to Baghdad, it was as if they pulled a plan off their shelf that said ‘U.S. invades Iraq.’ They effectively launched a counter-invasion [and flooded southern Iraq] with Badr Corps and their own Iranian operatives. So they are immediately positioning themselves with the Shia community. They have tremendous influence, and we miss a lot of this.”

Later in the war, Iran began to violently challenge U.S. forces. Around 2005, Crist says, Iran saw further opportunity in the growing insurgency, and began funnelling advanced improvised explosive devices, to friendly militias to target coalition forces. Around 2006, he says, the U.S. began to arrest Revolutionary Guards officials and operatives in Iraq. Ultimately, President Nouri al-Maliki’s efforts to rein in Shiite militias quieted Iranian activity until around 2010, when some of those same militias targeted the Green Zone.

Post-2003, Bdaiwi says, the belief pervades Iraqi political culture that Iran exerts considerable influence over Shiite politicians and Iraq’s southern provinces. “There is a running joke that elections take place in Baghdad, but the real decision is made in Tehran.”

Complications of Influence

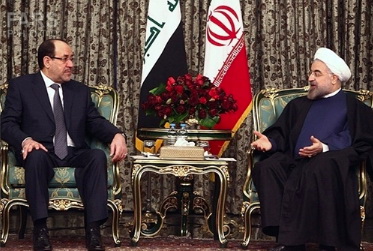

Today, Iran wields strong influence in Iraq, although the relationship is complex. “It’s very close, but it’s not a push-button influence,” Salem says. “They are certainly the most influential external player by a long shot.” But Iraq, he says, is not weak, since Maliki and the Iraqi government have massive oil revenues and Iraq’s oil output has surpassed that of Iran. While Iran has old and deep relationships with Maliki and with other Shiite leaders and parties, Iraqi Shiites also have their own strong identity and ambitions. “They certainly don’t see themselves as secondary to [Iran]. Iraqi Shiites are eager to build up their economy and their state so it can stand up on its feet and be independent. They are proud Shiites, and they are well aware that they are the original Shiites.”

Notably, Iraq’s Shia clergy have a different conception of the relationship between mosque and state then that of Iran’s leaders. “If we look at Najaf today,” says Bdaiwi, “there are four grand ayatollahs, four paramount authorities, who command the respect of millions of Iraqis, and non-Iraqis as well. None of them subscribe to the velayat-e-faqih, or ‘guardianship of the jurist,’ which underpins Iran’s political system.” The Iraqi clergy, he says, and particularly the four grand ayatollahs in Najaf, believe that the jurist who represents the 12th Imam has only partial authority, whereas Ruhollah Khomeini and his students argued that it was absolute. They do, however believe that religion should play a role in politics, as demonstrated by Grand Ayatollah Ali Al-Sistani’s recent calls for Iraqis to join the security forces to fight ISIS terrorists in Iraq’s north.

Iran has also built strong connections with Iraq’s Kurdish leaders, Crist says. “The Iranians are very good at maintaining ties with a lot of different groups so that they can position themselves no matter what happens.” But Iran, he says, remains concerned about the prospect of an independent Kurdistan, and how that eventuality would affect its own Kurdish population.

Iran is not keen to see Iraq fall apart, Crist says, but the recent ISIS incursion into Iraq’s north has presented opportunities for Iran, and has “caused a revitalization of Shiite militias, which Maliki didn’t want, but now needs.” If Iraq does fall apart, he says, Iran sees militias as an avenue for control. If Iran sustains its ties with Iraq’s Kurds and its Shiite militias it will be well positioned in the event of national collapse. Iran’s supreme leader Ali Khamenei, he says, views ISIS as a creation of the West, designed to undermine both its Syrian ally Bashar Al-Assad and the Iraqi government.

The crisis in Iraq’s north also represents a major setback for Iran, Salem says. When U.S. forces withdrew from Iraq, Maliki controlled Iraq, Bashar Al-Assad controlled Syria, and Hezbollah dominated Lebanon. Now it is left only with pieces of each region under its influence. From Iran’s perspective, ISIS rode the wave of an Iraqi Sunni uprising against the Maliki government, which Turkey or the Gulf States may have aided in part. In Iraq, he says, “I imagine they blame Maliki for part of this, but they are worried that, if they replace Maliki, will there be anyone tougher than Maliki? Will they gamble with some new leader? It’s not clear what the Iranian position is yet.”

Click HERE to read more

Be the first to comment