This article was last updated on April 16, 2022

Canada: ![]() Oye! Times readers Get FREE $30 to spend on Amazon, Walmart…

Oye! Times readers Get FREE $30 to spend on Amazon, Walmart…

USA: ![]() Oye! Times readers Get FREE $30 to spend on Amazon, Walmart…

Oye! Times readers Get FREE $30 to spend on Amazon, Walmart…

Given this tweet from Donald Trump:

There is nothing that I would want more for our Country than true FREEDOM OF THE PRESS. The fact is that the Press is FREE to write and say anything it wants, but much of what it says is FAKE NEWS, pushing a political agenda or just plain trying to hurt people. HONESTY WINS!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) August 16, 2018

…I thought that it was a good time to look at the most recent report from Freedom House on global press freedom and see where the United States stands in comparison to other nations in the world.

In Freedom of the Press 2017 , Freedom House assesses media freedom using common criteria for all nations using more than 90 analysts who gather information from field research, professional contacts, reports from local and international NGOs, government bodies and both domestic and international news media. A total of 23 methodological questions are divided into three categories; the legal environment, the political environment and the economic environment. Each of the 23 questions is further broken down into key aspects that give a full assessment of press freedom.

Here is a breakdown of each of the environments:

“1.) Legal Environment: encompasses an examination of both the laws and regulations that could influence media content, and the extent to which they are used in practice to enable or restrict the media’s ability to operate. We assess the positive impact of legal and constitutional guarantees for freedom of expression; the potentially negative aspects of security legislation, the penal code, and other statutes; penalties for libel and defamation; the existence of and ability to use freedom of information legislation; the independence of the judiciary and official regulatory bodies; registration requirements for both media outlets and journalists; and the ability of journalists’ organizations to operate freely.

2.) Political Environment: encompasses the degree of political influence in the content of news media. Issues examined include the editorial independence of both state-owned and privately owned outlets; access to information and sources; official censorship and self-censorship; the vibrancy of the media and the diversity of news available within each country or territory; the ability of both foreign and local reporters to cover the news in person without obstacles or harassment; and reprisals against journalists or bloggers by the state or other actors, including arbitrary detention, violent assaults, and other forms of intimidation.

3.) Economic Environment: encompasses the structure of media ownership; transparency and concentration of ownership; the costs of establishing media as well as any impediments to news production and distribution; the selective withholding of advertising or subsidies by the state or other actors; the impact of corruption and bribery on content; and the extent to which the economic situation in a country or territory affects the development and sustainability of the media.”

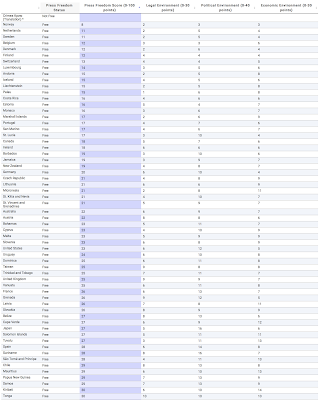

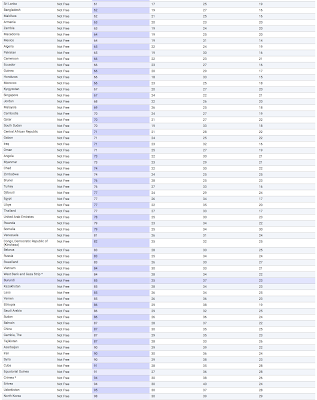

A lower number of points is allotted for a more free situation while a higher number of points is allotted for a less free environment. A score of between 0 and 30 results in a press freedom status of “Free”, a score of 31 to 60 results in a status of “Partly Free” and a score of between 61 and 100 results in a status of “Not Free”.

Of the 199 nations and territories that were assessed for the 2017 report, 61 or 31 percent were classified as “Free”, 72 or 36 percent were classified as “Partly Free” and 66 or 33 percent were classified as “Not Free”. A total of 13 percent of the world’s inhabitants live in nations with a “Free” press, 42 percent live in nations with a “Partly Free” press and 45 percent live in nations with a “Not Free” press. The percentage of people that live in nations with a “Free” press remains at its lowest levels since Freedom House began to incorporate population data into its annual analysis in 1996.

Here is a table showing the nations with a press freedom status of “Free” and their scores:

It is interesting to note that the United States has a score of 23, putting it in the lower middle of the “Free” nations. By way of comparison, Russia’s score of 83 and China’s score of 87 puts them significantly into the “Not Free” category as shown here:

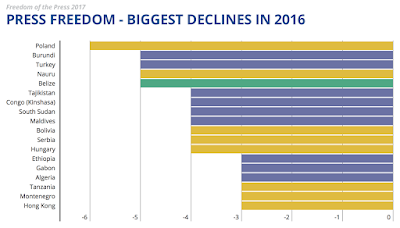

Here are the nations with the largest declines in press freedom over the past year:

Let’s now take a closer look at how the United States scored in 2017 and some problem areas facing the U.S. press. The United States is home to one of the world’s largest media sectors which have significant domestic and international reach. Freedom of the press remains relatively high thanks to constitutional safeguards, however, the federal government has been involved in a series of attempts to identify the sources of leaked information by putting legal pressure on journalists and through the extension of surveillance. The fracturing of the American media audience is also problematic given that media consumers favour obtaining their news only from sources that reinforce their political opinions.

Here is an outline of the issues facing the American news media political environment from the report:

“While self-censorship among journalists remains relatively rare in the United States and official censorship is virtually nonexistent, an increasing number of news outlets are aggressively partisan in their coverage of political affairs. The press itself is frequently a source of contention, with conservatives and liberals alike accusing the media of bias. The appearance of enhanced polarization is driven, to some degree, by the influence of all-news cable television channels and online-only outlets, many of which display an obvious editorial slant to the right or left. The popularity of talk-radio shows, whose hosts are primarily conservative, has also played an important role in media polarization. Nonetheless, most U.S. newspapers make a serious effort to keep a wall of separation between news reporting, commentary, and editorials. Most terrestrial broadcasters and major news agencies similarly avoid partisan reporting.

Media polarization became a source of controversy during the 2016 presidential campaign due in large part to the emergence of self-described “alt-right” news sites—purveyors of alternative right-wing perspectives on critical issues, including conspiracy theories, outspoken nationalism, and harsh views on women and minorities. As a candidate and as president-elect, Trump interacted with such outlets while accusing the mainstream news industry of bias against his campaign.

The Obama administration came under fire for effectively limiting journalistic access to federal officials, as well as official events. The president held fewer press conferences in his first term than did his predecessors, although he held a substantial number of meetings with small groups of usually friendly journalists. Journalists complained of an environment in which officials are less likely to discuss policy issues with reporters than during previous administrations, noting that “minders” representing the administration often sat in during meetings involving reporters and federal officials.

While foreign journalists are generally able to report in the United States with few impediments, from time to time there are cases of foreign journalists being denied entry to the country, usually on the basis of vague national security rationales.

In recent years there have been few physical attacks on journalists in reprisal for their work. However, journalists covering demonstrations or other breaking news events are occasionally denied access or even detained briefly by police. A number of journalists, documentary filmmakers, and other media workers were arrested or detained, and occasionally roughed up, while covering protests in 2016, especially those related to oil pipeline construction and police shootings of African American civilians. Serious felony charges were filed against the journalists in some cases, but they were typically dropped or rejected by the courts.

The press also faced increased hostility from politicians and the public in the context of the elections, with Trump in particular repeatedly accusing major outlets and individual journalists of lying, and hurling epithets such as “illegitimate,” “disgusting,” “slime,” and “absolute scum.” The temper of his attacks—which observers criticized as an attempt to undermine trust in the media and support for their traditional watchdog role—escalated when the Washington Post, the New York Times, and other outlets launched fact-checking features that revealed a large number of inaccuracies and exaggerations in Trump’s campaign assertions. Journalists were also harassed and intimidated during Trump campaign rallies, sometimes with the encouragement of the candidate or his subordinates, and the campaign temporarily barred some outlets from its events.” (my bolds)

Lastly, here is one of the key issues facing the news media economic environment in the United States:

“Media ownership concentration is an ongoing concern in the United States. While they are prohibited by FCC rules from owning more than one top-four local television station in any one market, many media companies have flouted these restrictions through “joint service agreements,” which allow them to operate stations that are owned on paper by others. The FCC enacted a rule in 2014 to curb the practice, holding that responsibility for selling 15 percent or more of a station’s advertising time amounts to an ownership stake. Consolidation of ownership has been spurred in recent years by a pattern in which media conglomerates spin off their newspaper units from their broadcast assets, and the separate companies then pursue mergers and acquisitions in their respective sectors. In April 2016, for example, the newspaper chain Gannett acquired Journal Media Group, which itself was the product of a 2015 merger; the new firm would control more than 100 dailies across the United States.” (my bold)

While much the liberal media likes to point out that press freedom in the United States is on the decline thanks to Donald Trump and his highly divisive campaign in 2016, there are other factors at play:

1.) the rise of the internet which has weakened the financial health of long-established media organizations

2.) the lack of a sustainable business model has diminished the production of local news and reduced support for in-depth investigative reporting

3.) the polarization of the media into competing outlets that openly pursue partisan agendas

4.) the Gawker/Thiel privacy lawsuit which helped bankrupt a media outlet

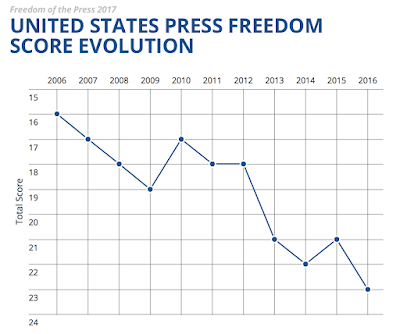

Let’s close with this graphic showing the declining press freedom score for the United States:

While the chances that the United States will turn into an authoritarian nation with a severely restricted press are slim, the long-term decline in press freedom in America sets a questionable example for the rest of the world given its dominance in the global news media. When politicians in other nations see America’s political leaders continuously criticizing their own nation’s news media, leaders around the world may seek to emulate the American example by further suppressing press freedom in their own spheres of influence.

Click HERE to read more from this author.

You can publish this article on your website as long as you provide a link back to this page.

Be the first to comment