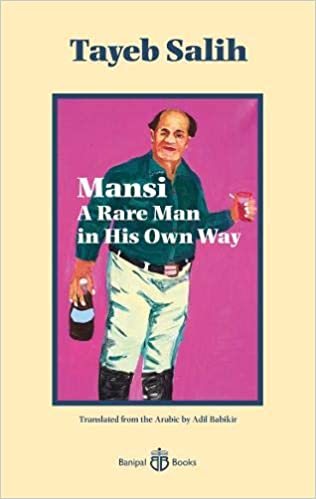

Earlier this year, Banipal Books published an English translation of acclaimed Sudanese author Tayeb Salih’s منسي إنسان نادر على طريقته (Mansi: A Rare Man in His Own Way), in Adil Babikir’s fluid and enjoyable translation:

Translator Adil Babikir notes, in his introduction and on the Banipal website, that when the book was initially published in 2004, three years before the author’s death, many mistook it for a fiction. The book doesn’t read like traditional memoir or biography; it’s fast-paced and interleaves Mansi’s life with Salih’s own in a way that is not chronological, but rather driven by the logic of nested stories.

Mansi himself makes an improbable real-life character. He was sometimes Ahmed Mansi Yousif, or Mansi Yousif Bastawrous, or sometimes Michael Joseph, and he played the part of buffoon and scholar, pauper and lord, Coptic Christian and observant Muslim. He pushed himself into situations with Queen Elizabeth and Samuel Beckett that made him seem a bit like Sacha Baron Cohen. And Mansi is also the sort of larger-than-life seducer who seems at least a bit reminiscent of Mustafa Saeed, from Season of Migration to the North.

But, Babikir assures us (and there is a photo in the opening pages of the book), Mansi was indeed a real man, if a rare one.

Why — when there is so much attention given to Season of Migration to the North (at least in literary and scholarly circles) — is there so little given, in English, to Tayeb Salih’s other literary works? Bandarshah, I believe, is out of print. And as for his nonfiction, I believe yours is the first translation?

Adil Babikir: It’s true that the Season has overshadowed all Salih’s other works, including his great novel Bandarshah. To me, the Season has drawn its popularity from its high drama and its novel tackling of the issue of colonialism, or the East-West relationship. Tayeb Salih once said in an interview that he had “redefined the so-called east-west relationship as essentially one of conflict, while it had previously been treated in romantic terms.”

Many people are tempted to see Bandarshah as victim to the phenomenal success of the Season. Interestingly, Tayeb Salih reiterated on many occasions his personal opinion that his best work was Bandarshah, not Season! Colonialism as a hot theme continued to feed the latter’s popularity, particularly in the West. Perhaps due to a thick shade of mysticism, some readers felt Bandarshah is a bit more complex than Season. To me it is just fascinating, even more poetic! After all, I tend to look to Salih’s works as interconnected threads.

Yes, Mansi is Salih’s first nonfiction to appear in English translation.

When did you first read Tayeb Salih’s work, and what impression did it make on you? And what was your journey to translating this book?

AB: I started reading Tayeb Salih at high school, beginning with his short story “A Handful of Dates,” his maiden work. I was intrigued by the powerful narrative and could feel the shock of the little boy — the narrator — upon seeing his idyllic innocent world falling apart before his very eyes. In my first year in college I came to read it again in Denys Johnson-Davies’ magnificent translation which, looking in retrospect, could have been one of the first reads that sparked my interest in literary translation. As a reader, my fascination with Salih continued ever since. I read all his works of fiction as they came out in the 1970s.

Starting from the late 1980s, Salih appeared every week on the last page of the London-based al-Majalla magazine and over the next ten years captivated readers with his fine writings on diverse topics, including literary criticism, political commentary and reflections on life. These series of writings were later published in a collection of ten volumes.

Mansi came out in weekly instalments, starting in 1988, before being collected together and published in 2004. It is a unique type of writing, a combination of biography, autobiography, political analysis, philosophical insight — with a great sense of humor and satire. Translating this work was a joyful experience. The biggest challenge was how to capture the tone, cadence and render the rich texture of the original.

I was surprised to find the book such a vibrant delight! I suppose because I found Naguib Mahfouz’s newspaper columns, by contrast, a bore. But Salih is writing a different sort of nonfiction, one with quick scene changes, digressions, plot reveals, and a lot of humor. What aspect of the book did you most enjoy, as a reader and as a translator?

AB: Part of the allure of Salih’s non-fiction comes from his skillful employment of fiction-writing techniques. But it is also derived from the rich references to Arabic classic literature, which are seamlessly woven into the fabric of his texts. Drawing on an almost inexhaustible repertoire, Salih adeptly uses historical anecdotes, philosophical reflections, and poetry to add depth and eloquence to his pieces.

In Mansi, and invariably in all his other non-fiction writing, including even political commentary, Salih skillfully employs fiction-writing techniques to weave texts that seem to slip through the borders of genres. His amazing ability to mould his ideas into a captivating, coherent, and well-knitted narrative is evident throughout this book. I believe all these factors worked together to make translating this work a memorable experience.

Like readers before me, I also found it hard to believe Tayeb Salih was not pranking me, since this Mansi is such a larger-than-life character. Are there other photos of him (outside of this one), or writing about Mansi? I thought perhaps there should be mention of him in the English press?

AB: I don’t blame you! Although Salih repeatedly pointed out that all the events in this book were “factual anecdotes,” many in the Arab world have misread the book as a work of fiction. The confusion is partly related to Salih’s writing style, I mean his skillful employment of fiction-writing techniques in all his writings.

But it also had to do with Mansi, who has a unique blend of traits typical of a fictional character. A man who lived with at least three different names, and who played at least eight real-life roles, from a porter to a university lecturer, and from a nurse to a clown. A penniless man who rose to the upper echelons of the British society and married a girl from a prominent English family, a descendant of Sir Thomas More. A man daring enough to cross all security and protocol barriers — presenting himself to Queen Elizabeth as the head of an official Egyptian delegation, and engaging in a public debate on a subject he knew little about with no less a historian than Arnold Toynbee.

I haven’t seen any mention of Mansi in the English press, but I heard and read Salih saying Mansi was a real-life friend.

This is also a part-memoir, as by giving a portrait of such a close friend, Salih is also giving us a portrait of himself — not his home life, but his work life, particularly his life on the road. Were there any surprises, for you, about the man himself? He was more playful than I had expected.

AB: A unique advantage of this book is that it provides a rare exposure to Salih’s personal life as it contains glimpses of his career years at the BBC, at UNESCO, and of his social encounters with friends in Cairo, Beirut, and other cities. Here, Salih comes out into the open without the usual camouflage of the fiction writer, unlike in his novels. Through the lens of this exposure, we see a highly satirical Salih with a keen sense of humour. We also see a collected person who remains unflappable in the face of the most delicate challenges.

As a keen reader of Salih, none of that came as a surprise to me. His political satire, for instance, captured the frustration of the Sudanese in the early 1990s as it decried the flagrant practices of the defunct regime of the Islamists in Sudan. “Where did those people come from? What kind of people are they? Were they not breastfed by mothers like everyone else? Don’t they love their country like we do? Then why do they seem to hate it? Why does it look as though they are bent on devastating it? Are they still dreaming of building on the dead body of poor Sudan an Islamic caliphate to which the peoples of Egypt, the Levant and the Maghreb, Yemen, Iraq, and the Arabian Peninsula should vow allegiance?”

The book is available as an ebook or paperback.

Click HERE to read more from this author.

You can publish this article on your website as long as you provide a link back to this page.

Be the first to comment