This article was last updated on May 25, 2022

Canada: ![]() Oye! Times readers Get FREE $30 to spend on Amazon, Walmart…

Oye! Times readers Get FREE $30 to spend on Amazon, Walmart…

USA: ![]() Oye! Times readers Get FREE $30 to spend on Amazon, Walmart…

Oye! Times readers Get FREE $30 to spend on Amazon, Walmart…

Alex Nowrasteh of the Cato Institute, which argues for open borders and amnesty, has published a posting at Cato’s blog that tries to refute a report authored by Karen Zeigler and myself showing just how bad the labor market is for native-born Americans. His efforts to refute our analysis are very odd. In some places he does not seem to have read the report. For example, in the first sentence of his short essay he says that our report claims that “immigrants are benefiting from the slightly recovering job market while natives are not.” We make no such claim. In fact, one of the bullet points in our report’s summary states: “Since the jobs recovery began in 2010, 43 percent of employment growth has gone to immigrants.” He goes on to write in the first paragraph that, “CIS would use that as evidence that immigrants are a drain on the economy.” Again, we make no such claim. In fact, my analysis says nothing about whether immigrants are a “drain on the economy”, to use his words.

In Mr. Nowrasteh’s second paragraph, he cites some research showing that immigration may reduce wages for the native-born — a subject that our analysis never even mentions. He then dismisses concern over job competition by asserting that the effects of immigration on the employment of natives are “small”. In contrast, on p. 14 of our analysis we cite six academic studies that have found that immigration does, in fact, reduce labor market opportunities for natives, particularly the young and minorities. In contrast to Mr. Nowrasteh’s categorical assertion that there is no significant negative impact, in our analysis we state that there is a debate among economists on the subject.

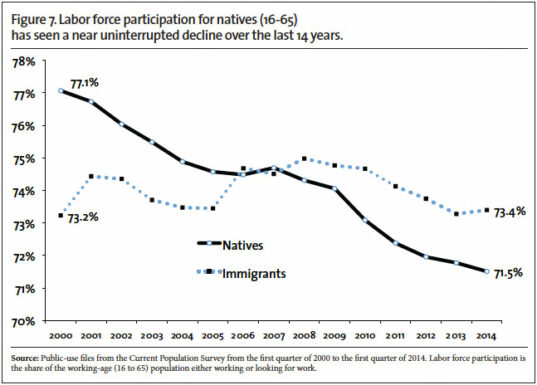

The central finding of our analysis is that when we look at the working-age (those 16 to 65) over the last 14 years, employment growth did not come close to matching natural population growth and the number of immigrants allowed to settle in the country. The 16- to 65-year-old population grew 25.7 million, but the number of working-age people with jobs increased only 5.6 million. Natives accounted for two-thirds of the 25.7 million increase in the size of the working-age population, but none of the net gain in employment over the entire 14-year period went to natives. As a result, the number of working-age natives not working is at or near historic highs and the share holding a job is at or near historic lows. Further, the labor force participation rate (working or looking for work) of natives shows a nearly 14-year uninterrupted decline.

The reason this has happened is, as we state in the second paragraph of our report: “because, even before the Great Recession, immigrants were gaining a disproportionate share of jobs relative to their share of population growth. In addition, natives’ losses were somewhat greater during the recession and immigrants have recovered more quickly from it.” Nowrasteh does not dispute any of these facts.

To the extent that there are policy implications, we make a straightforward observation that the enormous number (58 million total) of working-age natives of all ages and skills not working is a clear indication that potential labor is not in short supply. The idea that labor is in short supply is one of the primary justifications for the Gang of Eight bill passed by Senate (S.744) that would have doubled the number foreign workers allowed into the country.

Nowrasteh’s main response to our analysis is, first, that there is nothing to be concerned about because “Unemployment rates for the native-born and immigrants move in the same direction.” Our analysis shows the same thing. But by itself this is not necessarily a good thing. For example, the unemployment rates for less-educated blacks and more-educated whites also move in the same direction as the economy expands and contracts, but the much higher starting rate and slower pace of improvement for blacks are seen as serious concerns. Moving in the same direction does not mean very much.

Equally important, the employment rate (share of working-age people holding a job) and labor market participation rate (share holding a job or looking for one) show divergent patterns for immigrants and natives, something Nowrasteh totally ignores. Figure 6 from our report shows that, while working-age natives once had a higher employment rate than immigrants, today it is a lower.

Figure 7 from our report also shows the divergent pattern when it comes to labor force participation for immigrants and natives. As we state in our analysis, the employment rate and labor force participation are measures of labor force attachment that are less sensitive to the business cycle than the unemployment rate, which we also report in the study. They are, in our view, more important measures of what is going on in the labor market. Figure 7 shows that the labor force participation of working-age natives continued to decline even after the recovery from the 2001 recession as well as after the jobs recovery that began in 2010. But this is not the case for immigrants.

Since these divergent trends in the employment and labor force participation rates of natives and immigrants are a central finding of our analysis, one might think that they would be a central part of his attack on our work. Instead, Nowrasteh seems to concede that a divergent pattern in the unemployment rate of immigrants and natives might possibly be a problem, otherwise why mention it? But then he never even discusses the divergent trends in the labor force participation rate of immigrants and natives.

His second response is to cite an NBER paper that found less-educated Mexican immigrants are more willing to move around the country than less-educated natives and this, he suggests, is why they got such a disproportionate share of employment growth. But this is no way refutes our analysis. In fact, it supports our findings. We make this very point in our report (p. 9): “By coming to this country, immigrants almost always see substantial improvement in their standard of living, no matter where in the United States they settle. This may make them more willing to move wherever there is job growth in the United States. Natives, on the other hand, may need significant wage incentives.”

We further point out that the willingness of immigrants to move may mean that businesses don’t have to raise wages in the way that they would if there was less immigration. The bottom line is that the possibility that immigrants are more willing to move where there is job growth is in no way inconsistent with our findings. In fact, it buttresses them by providing a possible explanation for them.

Our findings indicate that something very important has been going on in the U.S. labor market. When we look at the working-age, all of the long-term job growth has gone to immigrants. At the same time, the number and share of natives not working has exploded. As we show in our analysis, the last 14 years have been a period of very high immigration and very weak job growth for natives. It is certainly not our contention that these facts settle the question of whether immigration is good for American workers. But it does challenge the argument that immigration, on balance, increases job opportunities for natives. The record number of working-age natives not working also makes clear there is no general shortage of labor in the United States, as many immigration advocates argue.

Click HERE to read more

All you’ve done is selectively pull data to show the 2001 tech bubble, a genuine private business bubble, rolled into the government caused housing bubble of 2008. You’re pretending that these show a normal trend and discounting both the recovery from the private bubble and the complete lack of recovery from the government caused one. Also, Immigrants and natives both trend the same directions at the same times.