Key to any economic recovery is an increase in household spending and, as we all know, much of household spending is supported by increases in consumer debt. A brief by John Krainer, a Senior Economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, entitled "Consumer Debt and the Economic Recovery"outlines the uncertain state of consumer finances and how this has impacted the ability of the economy to recover after the Great Recession.

Since 2008, total household liabilities have fallen by about 7 percent or nearly $1 trillion, a major downward adjustment that was related to the "wealth shock" due to the collapsing housing market. According to the Federal Reserve Flow of Funds data current to the end of 2011, total home mortgage credit dropped by $733.7 billion between 2007 and 2011 and consumer credit dropped by a net $28.7 billion over the same period.

Generally, households consume goods by borrowing against future income so that they can consume goods in the present. As long as the perception of household wealth and income remain positive, consumer borrowing will continue to take place. However, when households experience a shock to wealth or income and those shocks appear to be for the long-term, they will reconsider the amount of debt that they are willing to take on. Some households will cut back on the amount of credit they are comfortable with whereas others (i.e. those households with unemployed members) may choose to keep borrowing through lines of home equity, however, even this tactic will end at some point as lenders become reluctant. The amount that consumers can borrow is largely dictated by the willingness of lenders to provide credit. The same factors that cause the wealth effect of households to disappear can result in losses for lenders.

Keeping the above in mind, there are three ways that household debt levels can decline:

1.) Households decide to consume less and save more.

2.) Households can walk away from debt through foreclosure or bankruptcy.

3.) Lenders can cut back lending, contracting the supply of credit.

In any case, the drop in credit has a direct impact on the total demand for goods and services and ultimately on economic growth. The relationship between consumer demand and credit is particularly important since approximately 70 percent of the U.S. GDP is connected to household spending. The latest data release from the U.S. Department of Commerce shows that real personal consumption expenditures increased 2.4 percent in the second quarter of 2012, down from 2.4 percent in the first quarter.

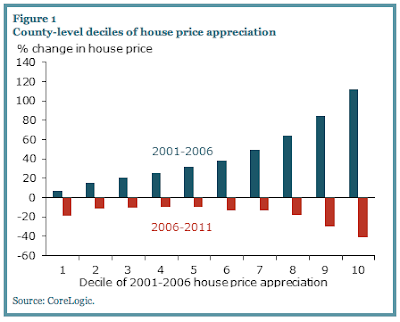

Since the Great Recession and the collapse in housing prices in 2006, as I noted above, households experienced a "wealth shock". This graph shows that in counties where real estate prices increased the most between 2001 and 2006, saw the greatest house price decreases during the 2006 to 2011 bust:

The households that experienced the biggest drops in house prices also experienced the largest declines in non-mortgage consumer debt, not surprisingly, those households that defaulted on their mortgages seeing the greatest drops in consumer debt.

Let's take a closer look at American consumer debt. In the fourth quarter of 2011, there was nearly $12 trillion in total consumer debt. About 70 percent of this was mortgage debt, home equity loans accounted for 10 percent, auto loans accounted for 7 percent and bank credit card balances accounted for 6 percent. Linking the consumer debt statistics to default history shows that borrowers who defaulted at some point over the period between 2001 and 2011 actually borrowed at a much faster rate than non-defaulters as shown on this graph:

The ramping up of non-mortgage debt occurred among younger borrowers and those with lower credit scores (i.e. subprime borrowers). As you can see on the graph, once the housing boom ended, defaulting mortgage borrowers reduced their non-mortgage debt at a far faster rate than non-defaulters, likely because they lost access to credit.

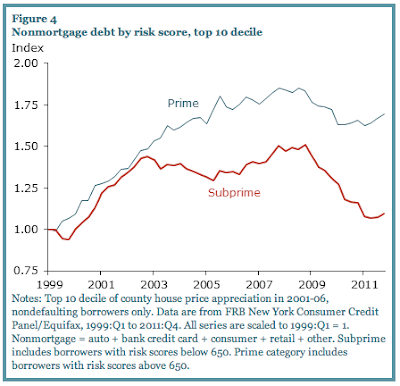

Among non-defaulting mortgage borrowers in real estate markets that experienced house price increases in the top ten percent between 2001 and 2006, the non-mortgage debt loads of subprime borrowers rose in pace with and then fell much more quickly during the Great Recession than their prime borrower counterparts as shown here:

The same pattern exists for non-defaulting mortgage borrowers in real estate markets that experienced house price increases in the bottom ten percent between 2001 and 2006. This shows one of two things:

1.) Subprime borrowers had less demand for credit than prime borrowers.

2.) More likely, lenders were less willing to lend to subprime consumers.

In summary, Mr. Krainer's research suggests that consumer non-mortgage debt deleveraging takes place as highly indebted households reduce debt loads when house prices fall. The most important factor in predicting the consumers that will deleverage the most is not the amount of the house price decline, rather, it is more closely tied to one of two factors; a history of mortgage default and a low credit score. This suggests that it is quite likely that tighter credit market conditions are cutting the flow of credit to consumers right across the United States. The restricted supply of available household credit will make it difficult for the United States economy to grow at more than its current tepid rate and, until the housing market shows signs of a robust recovery, the situation is unlikely to improve.

Click HERE to read more of Glen Asher's columns

You can publish this article on your website as long as you provide a link back to this page.

Be the first to comment