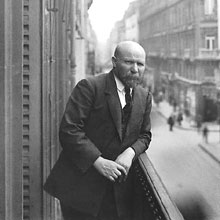

The pale, almost sepulchral figure of Rabindranath Tagore standing among tangerine trees and under marmalade skies. Well, not quite. But take a look at the astounding 1921 photograph of the Indian poet in a Parisian rose garden on the right and you’ll know what kind of exhibition is in town.

The pale, almost sepulchral figure of Rabindranath Tagore standing among tangerine trees and under marmalade skies. Well, not quite. But take a look at the astounding 1921 photograph of the Indian poet in a Parisian rose garden on the right and you’ll know what kind of exhibition is in town.French banker Albert Kahn’s mission in life was to establish a social-anthropological visual diary of the peoples of the world. And between 1909 and 1931, Kahn did exactly that by sending teams of photographers all across to assemble the ‘Archives of the Planet’. So what was his weapon of choice? The new technology of the autochrome.

While there were photographs — as well as cinema reels — depicting colour before the autochrome, these were laboriously hand-tinted and clearly ‘doctored’. The autochrome process, using potato starch and the basic dyes of orange, green and violet acting as colour filters, turned the (black and white) negative into a shimmering version of captured reality in the developing stage. Patented by Louis Lumiere (one of the brothers who showed the first moving images in the world), the technology lasted for some 30 years, dying out with the advent of Kodak’s colour film.

Alain Lavital, of the French luxury house Louis Vuitton that has brought a selection of autochromes of Kahn’s ‘Archives of the Planet’ collection, points out how radical the technology was. “The point was to bring colour and vitality to black and white photography. The aim was to get as close to reality as possible.”

Looking at the hauntingly tinted shades of the Taj Mahal, a photograph taken in 1913 by Stephane Passet, who spent more than a year chronicling “everyday Indian life” across the north-western plains of the country, the ‘realism’ is barely perceptible. The hints of yellow and the overgreyness of greys have more than a touch of the fantasy about them.

But then, the autochrome serves a different aesthetic and functional purpose: “Roland Barthes used to say, ‘The most important thing is that a picture has a strong impact when we look at it, not because of the depicted object, but because of the time it strongly focuses on,’” says Yves Carcelle, chairman and CEO of Louis Vuitton, whose bags Kahn would specially order for his globe-trotting photographers. “The autochrome was totally in line with this idea of ‘catching time’.”

What really strikes the viewer looking at these ‘unnatural’ pictures is how he is forced to rethink the way to look at the past. Close your eyes and conjure up a mental photo of a dhoti’n’shawl-clad priest from the same era standing on the temple courtyard with an old gentleman peering from behind. You know the year is 1914 and with the date firmly in mind, you are bound to see the image in ‘pre-modern’ black and white. Open your eyes and see the photo on the far right and you’ll realise, naturally depicted or not, the autochrome forcefully telling you that the past has always been in colour.

Yes, Tagore when standing in the garden of Albert Kahn, unnatural as the image may look, was surrounded by light red roses on a summer 1921 morning.

Be the first to comment