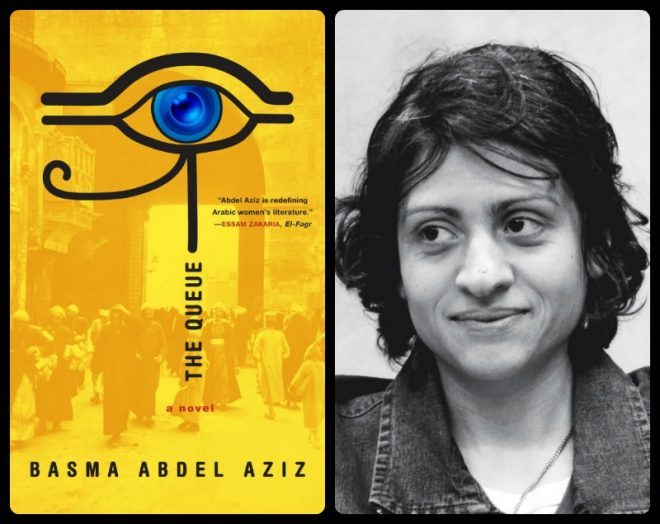

This short essay by Basma Abdel Aziz, translated by Elisabeth Jaquette, originally ran last summer in For Books Sake. It appears here on ArabLit as a closer to Women in Translation Month (#WiTMonth):

In an unnamed Middle Eastern city, in the aftermath of a failed uprising, an authority known as the Gate has risen to power Citizens are required to obtain permission from the Gate for even the most basic of their daily affairs, yet the building never opens, and the queue in front of it grows longer and longer.

Egyptian author Basma Abdel Aziz tells us more about the real-life queue that inspired her debut novel, a book that’s already been compared to dystopian classics including Kafka’s The Trial and Orwell’s 1984…

I began writing The Queue in September 2012, shortly after returning to Egypt from France. One sunny day, I went to Downtown Cairo, where numerous battles between revolutionaries and security forces had taken place since the revolution began in January 2011.

While walking down a main street, I came across a long queue of people waiting in front of a closed governmental building. The gate to the building would certainly open shortly, I thought to myself; after all, it was nearly midday.

Two hours later I walked back the way I came, only to find the same people standing exactly where they had been. They hadn’t moved. There were more of them now, yet the gate was still closed.

“I DIDN’T KNOW WHAT THEY WERE WAITING FOR, AND WHY THEY DIDN’T LEAVE”

Some sat on the ground, some leaned against cars parked by the sidewalk, and some had retreated under the shade of nearby trees, seeking shelter from the heat. I didn’t know what they were waiting for, and I didn’t understand why they didn’t leave. Noon had turned into afternoon, yet nothing had changed.

The people seemed bound there – to that patch of ground, and to the gate which was still closed – by the hope of having their needs met. I thought the scene would make a good short story, one I might include in the next collection I wrote, so I wrote down my observations on scraps of paper I always keep in my bag, and when I got home I started writing.

I was primarily interested in what all these different people in this strange queue had in common; there didn’t seem to be any connection between them.

Some seemed financially comfortable, while others looked poor, there were women and men, elderly and young people, and even children playing nearby.

I wondered why they stood there so long in vain. Why didn’t any of them speak up in protest or frustration about the delay; why didn’t anyone suggest they all leave?

“THE QUEUE EXTENDED THROUGH THE NOVEL, CROSSING INTO OTHER CITIES”

This thread was just the beginning, not for a short story, as I had intended, but for my first novel: The Queue. I spent two whole months writing without pause; I was seized by the desire to follow the fates of these characters that had appeared and taken shape on the page.

I didn’t plan it in advance, or sketch out their lives before starting to write. The queue extended through the novel, crossing into other cities, and my imagination extended further and further with it.

I spent eleven hours a day with the queue and the people waiting in it; I experienced their relationships and interactions, until I nearly felt like I had become one of them.

I developed patience and perseverance, just like the characters who rescheduled their lives so they could stand in front of the Gate and fruitlessly wait.

ON THE VERGE

It reached the point that I felt I was on the verge of becoming someone like many of the characters, a dutiful and submissive citizen whose life is dictated by totalitarian authority.

The closed gate slowly came to symbolize a regime that represses people, determines their behavior, turns them into identical copies of one another, and strips them of their will.

Meanwhile, the queue became a parallel society for which the people waiting had exchanged their normal lives: they began to eat, drink, sleep, conduct business, negotiate with each other, and worship there.

The protagonist of the novel is a man in his late thirties with a bullet lodged in his body. He cannot have it removed without permission from the authorities, who, of course, are represented by the Gate.

People rose up against the regime in power, and as a result, the Gate closed. It hasn’t opened since, as if it were punishing them; as long as the Gate is closed, people’s affairs are delayed.

The number of citizens gathered in front of it, each with his or her own aim, begins to multiply. Some want certificates certifying that they are True Citizens so they can find a job, some want medical treatment, and some simply want a permit to buy food.

“NO MORE THAN SHADOWS OF THEMSELVES”

In writing The Queue, I drew on my experience in psychiatry, my specialization and the field in which I work. I also drew on my later studies in sociology, to establish the means by which authority dominates and controls citizens.

I examined the complex mechanisms which, in the end, make people accept the reality they find themselves in, even if it is dire. I also built on my experience working with victims of torture.

For over ten years I have worked at El Nadeem Centre, which offers support and psychological rehabilitation for those who have been subjected to torture in police stations and detention camps.

I have seen with my own eyes how major psychological trauma can change people. I have witnessed how continuous repression and humiliation can drive them to become no more than shadows of themselves, not venturing beyond the lines their oppressor has drawn for them.

RULER AND RULED

In both my fiction and my academic writing, I have long been interested in the mutually constitutive roles of ruler and ruled. I am intent on exploring how this manipulates people’s fates, and am determined to resist the ways it reshapes their understanding of the world.

Egypt is currently going through a tumultuous period, but I believe this has the potential to inspire writers and thinkers, and motivate them to produce exceptional creative and intellectual work.

This essay originally appeared on For Books Sake.

Click HERE to view more.

You can publish this article on your website as long as you provide a link back to this page.

Be the first to comment