From the early ‘90s until 2000, there was a high cost involved with buying a diamond — and we’re not talking about the price tag.

If there was ever a purchase that you’d want to be proud of, diamonds would be it. After all, they’re exchanged as a symbol of love and commitment, and passed down through generations. But conflict diamonds — diamonds mined in a war zone to finance militant activities — cast a shadow on the glamorous world of luxury jewelry. Unfortunately, if your diamond was sourced in a war-torn country like Sierra Leone, Angola, or the Democratic Republic of Congo in the ‘90s, it could be a symbol of something much more dismal.

Amidst the growing consciousness of consumers and brands alike, the industry has changed — a lot. In 2000, the Kimberley Process (KP) was established to act as a global trade authority against conflict diamond mining. Today, it represents 81 countries, with the European Union counting as one unit, and is responsible for nearly eradicating the practice, preventing around 99.8% of the global production of conflict diamonds, according to the organization’s website.

But while conflict diamonds, or the current lack thereof, are often discussed in open forum, anyone outside of the jewelry business is probably out of the loop on the opposite: ethical and sustainable diamonds. A Google search might send you to vague explainers or a commerce page for how to shop them, but to really get to the bottom of what ethical and sustainable diamonds are, you have to dig a little further.

“There’s a lot of dialogue around conflict-free and all of that. For us, it’s not about being just being conflict-free — that’s not enough,” says Kristen Lawler-Trustey, PR Manager at Forevermark, the consumer-facing division of the De Beers Group. “It’s more about making a positive impact.” To do so, the De Beers Group launched a partnership with the country of Botswana, where one of the company’s largest mines is located, back when diamonds were first discovered there over 50 years ago. The alliance, known as Debswana, has successfully employed over 13,000 local residents, paved 6,000 kilometers worth of roadways, and built a number of free health care and education institutions for the residents in surrounding areas. The De Beers Group Orapa Mine, their largest mine — and the largest open-pit mines in the world — contributes to a large portion of that, not to mention a whole hell of a lot of diamonds.

“Diamonds are nature’s beauty and mining them is the cleanest form of mining,” Lawler-Trusty continues. “There are no harmful chemicals used to damage the environment.” And their goal is to keep it that way. As a rule, De Beers and Forevermark promise to dedicate six acres for every acre they use in the mining process. “We try to return the Earth to a state as close as possible to how it was before we found it.”

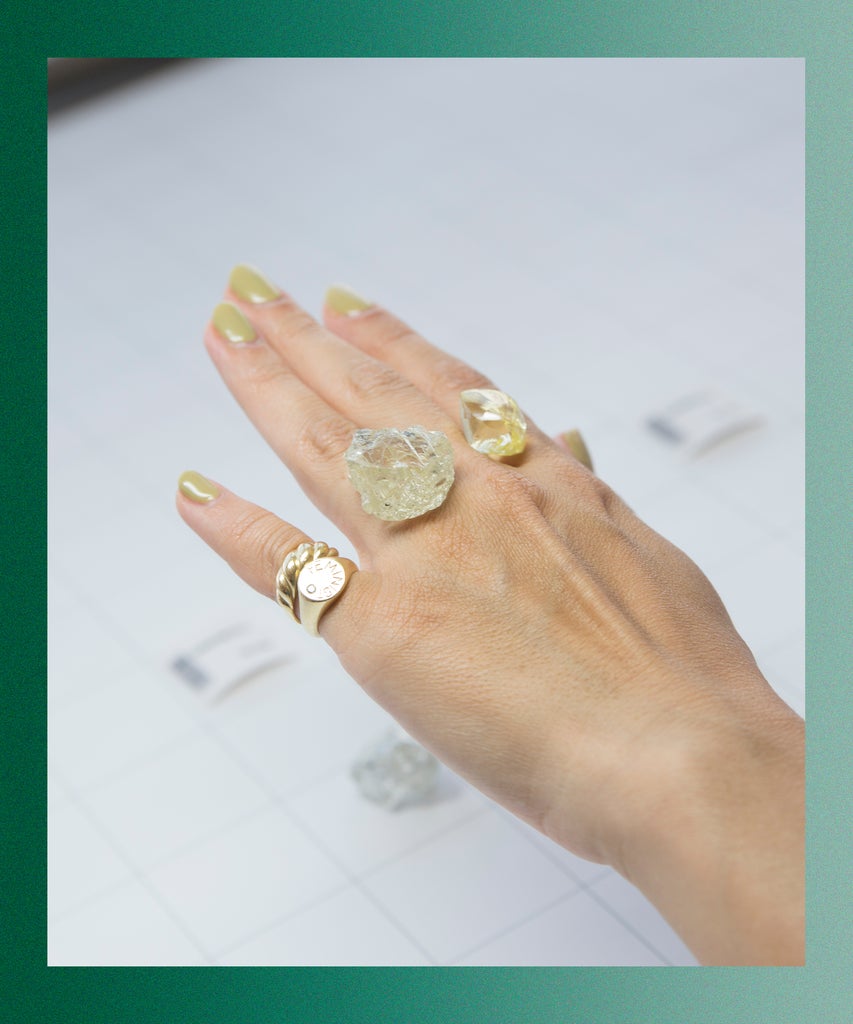

The actual process of mining and producing an ethical diamond is not very complicated. “When diamonds are unearthed, they are in their rough form, which is how they are when they’re sent to our De Beers global headquarters in Botswana.” When the company started mining in Botswana, they moved their headquarters from London to Botswana in an effort to, again, promote business in the country. Their global headquarters also sort diamonds mined in Namibia, South Africa, and Canada. “At that point, the rough diamonds are set aside for their characteristics of beauty. They have to meet certain criteria within the four C’s,” she says, but the difference between a Forevermark diamond and a lesser one is what’s criticized after carat, cut, color, and clarity. “Two diamonds might have the same beauty crisis, the same criteria in the four C’s, so on paper, they look like the same diamond. But we use the discretion of our experts because one diamond can be more beautiful than another.”

Ten times a year, diamonds are sent to the company’s sight-holders, or as the industry calls them, diamantaires. Basically, these are the cut experts who take a rough diamond and turn it into the polished gems we’re used to seeing on a left ring finger. “At Forevermark, we have just a handful of diamantaires that we work with that are certified to cut and polish to the exact standards of Forevermark.”

Once they’ve been cut, they’re sent to the Forevermark Institute with locations in Antwerp, Belgium; Maidenhead, UK; and Surat, India to be graded by the brand’s specific standards and later deemed up to snuff for the Forevermark inscription. According to a document on the Forevermark diamond journey, “Forevermark has a 17-step process, which includes scanning them in proprietary machines to check for their authenticity, carat weight, and symmetry.” Only 1% of all diamonds in the world pass the test.

As for the lab-grown diamond option, Forevermark isn’t looking to change things anytime soon. “Being a natural product is where the value is. Diamonds are finite; they’re precious; they’re straight from the earth. Any natural diamond, it already exists.”

We’re not yet convinced that either lab-grown or natural diamonds are 100% sustainable. After all, when you’re producing some 142 million carats of diamonds worldwide per year — according to a Statista study from 2019 — finding a way to maintain sustainability every step of the way is hard, if not impossible, to accomplish. Between the community building and the ecosystem repair, one thing is clear: Forevermark and De Beers Group are certainly making strides toward a brighter, more dazzling future for diamonds.

Click HERE to read more.

You can publish this article on your website as long as you provide a link back to this page.

Be the first to comment