Now that elected and non-elected officials around the world have gained the knowledge that they can suspend our rights and freedoms without significant repercussions (in most cases) because of a health threat, I believe that the next existential threat that the our overlords will use as an excuse to suspend our freedom will be linked to the threat posed by climate change. Since this threat is not at the forefront of most people's lives, governments will have to use what would have ordinarily be considered extreme means to get their citizens to change their behaviours when it comes to the consumption of greenhouse gas-emitting hydrocarbons just as they used extreme means to alter human behaviour during the pandemic. Let's look at one of these means that has the potential to change our patterns of consumption.

A very recent article on Nature Sustainability looked at one method that could be used to mitigate climate change. In the article "Personal carbon allowances revisited" by Francesco Fuso Nerini et al, the authors open by noting that the current planned climate policies will not meet the target of "well below 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels" and the 1.5 degree Celsius temperature increase that was ultimately agreed to in the Paris Agreement. Here is a quote from the paper with my bold:

"Thus, although many countries have made pledges of net-zero emissions by 2050, implemented policies and pledges are insufficient to deliver the Paris Agreement ambition of limiting global warming to well below 2 °C."

In fact, according to the authors, in May 2021, Climate Action Tracker estimated that current global climate policies would lead to a temperature rise of 2.9 degrees Celsius which, if true, will give governments the perfect excuse to enact extreme and previously unthinkable measures just as they have during the COVID-19 pandemic.

One of the proposals to limit carbon emissions is the use of personal carbon allowances or PCAs. Under a PCA system, all adults would receive an equal tradable carbon allowance that would reduce over time in line with their government's climate targets. There are two main ways of utilizing PCAs with a host of variations between the end points:

1.) A selective PCA – the allowance would cover around 40 percent of energy-related carbon emissions in high-income nations which would include individuals' carbon emissions related to travel including commuting, household heating, water heating and electricity consumption.

2.) A comprehensive PCA – the allowance would cover a far more comprehensive economy-wide emissions including food, services and consumption-related carbon emissions in addition to the aforementioned sources of carbon emissions.

An individual's PCA balance would decline with every payment for transportation (i.e. gasoline), home heating oil, electricity and other uses of carbon-emitting fuels. People who experienced a shortage in their PCA could purchase additional units in the personal carbon market from individuals who had a surplus in their PCA account.

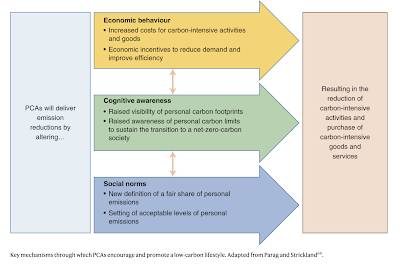

The authors note that PCAs are envisaged to deliver carbon-emissions-related behavioural change by way of three interlinked mechanisms as shown here:

Proponents of PCAs believe that, by assigning a visible carbon price to the purchase and use of fossil fuels, an individual's consumption behaviour will be changed since they will no longer have access to an infinite volume of fossil fuels.

There are three key technological barriers that must be solved before a PCA system is implemented:

1.) What technology is needed to manage personal carbon allowances?

2.) How will people keep track of their personal carbon allowance?

3.) How would personal carbon allowances be traded?

There are additional issues facing a PCA reality:

1.) Low social acceptability because of the complexity of the scheme and its potential to result in unfair distribution.

2.) Distributional impacts where low-income households would have surplus in their PCA since they consume less energy and high-income houses would have a deficit in their PCA since they consume more energy, necessitating the purchase of additional units.

In the past, consumers were reluctant to adopt a PCA program in part, because of privacy concerns. Here is a quote from the paper regarding that issue with my bolds:

"In particular, during the COVID-19 pandemic, restrictions on individuals for the sake of public health, and forms of individual accountability and responsibility that were unthinkable only one year before, have been adopted by millions of people. People may be more prepared to accept the tracking and limitations related to PCAs to achieve a safer climate and the many other benefits (for example, reduced air pollution and improved public health) associated with addressing the climate crisis. Other lessons that could be drawn relate to the public acceptance in some countries of additional surveillance and control in exchange for greater safety. For instance, in many countries, mobile apps designed for COVID-19 infection tracking and tracing played an important part in limiting the spread of the pandemic. The deployment and testing of such apps provide technology advances and insights for the design of future apps for tracking personal emissions. . Recent studies show how COVID-19 contact-tracing apps were successfully implemented with mandatory schemes in several East Asian countries, such as China, Taiwan and South Korea. In these countries, the apps assessed each user’s travel history and health status, playing a key role in tracking infections. These unique natural experiments give insights into possible strategies to use apps to track PCAs. For instance, the many digital contact-tracing algorithms that were developed and tested provide initial valuable information for the design of future apps that—for example—estimate emissions on the basis of tracking the user’s movement history."

So there you have it. Thanks, once again, to the COVID-19 pandemic, we now have a template for smart phone-based apps that could be used to track our use of fossil fuels and our carbon emissions.

Here's one final quote from the paper:

"Finally, advances in digitalization and AI for sustainable development promise to shrink implementation costs and logistical challenges for PCAs—and to improve personalized feedback, information and advice. Recent advances in smarter home and transport options make it possible to easily track and manage a large share of individuals’ emissions. Evidence from the roll-out of smart meters and informative displays can be used to design feedback that is highly effective in engaging individuals to reduce their energy-related emissions. Furthermore, AI breakthroughs combined with very high ownership of smartphones will allow the low-cost development of new personalized apps to account for PCAs and trade personal emissions. For instance, machine-learning algorithms could be trained to automatically gather all the available information on someone’s emissions, and to fill data gaps and accurately estimate an individual’s carbon emissions on the basis of limited data inputs such as stops at petrol stations, check-ins at venues and travel histories. AI could be especially beneficial for PCA designs that also include food- and consumption-related emissions. Many voluntary smartphone apps can already capture personal travel and dietary behaviours for estimating carbon emissions and potential health consequences. Algorithms in those apps can intelligently understand the mode of transport on the basis of the user’s speed and trajectory, and can estimate food-related emissions on the basis of purchasing habits. More importantly, machine learning could also support our understanding of what information and advice are most effective for promoting behaviour change through PCAs."

In case you were wondering, there actually has been a trial of PCAs in the United Kingdom over 4 weeks in June 2011 as shown here:

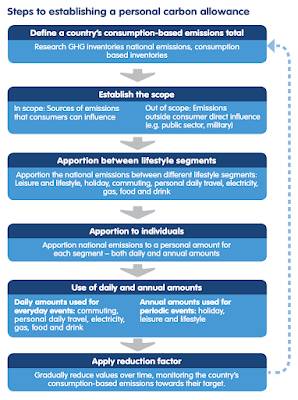

Here is a graphic showing how the PCA was established:

The annual personal allowance for the PCA was 7.3 tonnes of CO2 equivalent per person which is equivalent to 19.9 kg of CO2 equivalent per person per day. The concept of a PCA received both good and bad reviews from consumers which I will cover in a future posting.

Given all of this information, it is not terribly surprising that the adoption of a personal carbon allowance scheme seems far less challenging than it did 20 years ago when the idea was initially brought forward as a solution to global climate change. It's just a matter of time until governments figure this out and use their newfound powers of behavioural modification to implement a system of personal carbon allowances that intrudes even further into what little remains of our private lives.

You can publish this article on your website as long as you provide a link back to this page.

Be the first to comment