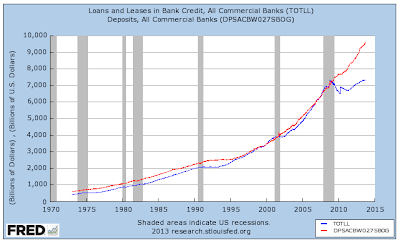

Here's a simple graph that goes a long way to explaining why the recovery has been so modest despite Mr. Bernanke's (and presumably Ms. Yellen's) Grand Experiment with interest rates:

The red line shows deposits with all commercial banks and the blue line shows loans and leases with all commercial banks in billions of dollars. Notice that until the Great Recession, the growth level in both deposits and loans and leases rose in tandem. It is quite apparent that the tight relationship between deposits and loans broke down in the early part of 2009.

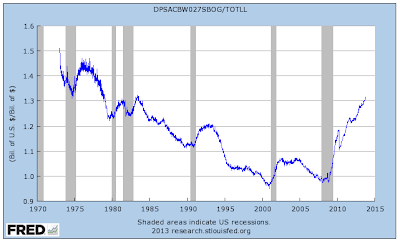

Here is a graph showing the loan-to-deposit ratio and how it has dropped to levels not seen since the early 1980s:

Right now, banks are only lending 76 percent of their deposits, a level last seen in June 1983. Also note that the drop in lending-to-deposits is showing no sign of abating.

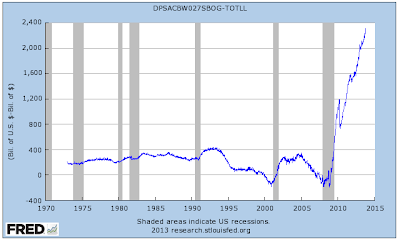

Let's flip loans and deposits around so that we end up with the ratio of deposits-to-loans as shown here:

Right now, banks are taking in $1.31 in deposits for every $1 that they loan to consumers and businesses. This is up quite markedly from $0.98 in deposits for every dollar that they loaned in May 2008.

Here is a graph showing the excess of commercial bank deposits over the amount banks have loaned:

Between 1973 and 2009, the excess of deposits over loans never rose above $433 billion and was generally below $400 billion. In contrast, in October 2012, deposits exceeded loans by $2.307 trillion, a new record amount. As you can see from the graph, the growth in deposits over loans is showing no signs of slowing down, a situation that looks very unhealthy.

So, what is it that banks are doing with the $2.3 trillion in deposits that they are not lending to consumers? Here is a look at the same loans and leases curve (in blue) with the reserve balances held by the Federal Reserve Banks (in red):

More than 6000 depository institutions maintain balances at the Federal Reserve Banks in reserve accounts. In October 2013, banks had just over $2.311 trillion on deposit with the Federal Reserve. This is money that is not loaned out and, in fact, after 2008, the Federal Reserve paid interest on these reserves. By paying interest on reserves, the Fed could both increase the level of reserves and maintain control of the federal funds rate by permitting the Fed to expand its balance sheet to provide the necessary liquidity to support financial stability.

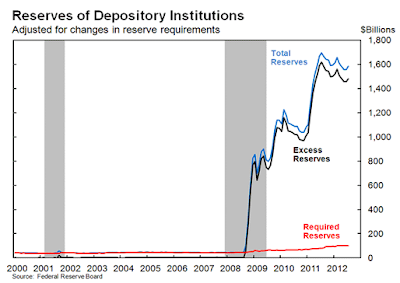

Just before the Great Recession, the required reserves (in red) averaged about $43 billion as shown here:

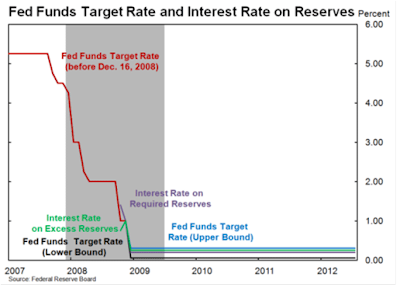

As you can see, that level changed once the Fed started paying interest on banks' reserves which have grown to a level in excess of $2.3 trillion, a 5350 percent increase in five years! As you can see on the black line which shows excess reserves, banks are using the Fed as their own bank largely because, since 2008, the interest paid on both required and excess reserves has stood at 0.25 percent, a completely risk free return particularly when compared to loaning to consumers and businesses. Prior to 2008, the Fed was not obligated to pay any interest on bank reserves, providing the commercial banks with absolutely no motivation to deposit excess monies with America's central bankers as shown here (in purple):

From the data presented here, it certainly appears that the Federal Reserve's policies are working against economic growth. When banks stop lending, the economy stops growing and the Fed appears to have made it way too easy for the commercial banks to invest in lower risk activities.

Click HERE to read more of Glen Asher's columns

You can publish this article on your website as long as you provide a link back to this page.

The payment of interest on excess reserve balances (but not required reserve balances), is contractionary & induces disintermediation within the non-banks (shadow banking system). Disintermediation is a term describing the outflow of funds or negative cash flow induced by the inversion in the short-end segment of the yield curve (where the remuneration rate is higher than Daily Treasury Yield Curve Rates 2 years out, i.e., higher than all money market rates). This is exactly the same phenomenon as occurred during the 1966 S&L crisis (when Reg Q ceilings finally breached wholesale short-term funding costs of the thrifts in the borrow short to lend long business model paradigm).

Bankrupt you Bernanke (He is entirely, directly responsible, for causing the Great-Recession, regulatory malfeasance notwithstanding), simply doesn’t understand the difference between money & liqucomment_ID assets. In fact, the entire Fed’s research staff is of the Keynesian macro-economic persuasion that maintanins a commercial bank is a financial intermediary. The source of this pervasive ignorance is that in almost every instance in which John Maynard Keynes wrote the term bank in the General Theory it is nec essary to substitutue the term financial intermediary in order to make his statements correct. I.e., stagflation (business stagnation accompanied by inflation) was predicted in 1958 – prior to the term being coined in 1965 (ex post facto). I.e., the proof is in the pudding (ex ante predictions, e.g., the denigration of the Phillips curve).