This article was last updated on April 16, 2022

Canada: ![]() Oye! Times readers Get FREE $30 to spend on Amazon, Walmart…

Oye! Times readers Get FREE $30 to spend on Amazon, Walmart…

USA: ![]() Oye! Times readers Get FREE $30 to spend on Amazon, Walmart…

Oye! Times readers Get FREE $30 to spend on Amazon, Walmart…

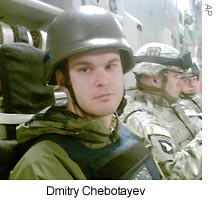

Novelist and translator Layla Qasrany remembers Dimitry Chebotayev, who died ten years ago in May:

All the cameras have left for another war…

—Wisława Szymborska, “The End and the Beginning”

There is something thrilling about dying before the age of thirty, to depart before illnesses and dental cavities makes ones life a legend, just like Jim Morrison, James Dean, Keats and Jimi Hendrix! So when Dimitry Chebotayev, an AP cameraman, died at 29 in the war zone of Iraq, my sorrow was tinged with jealousy, for that year I was turning forty, I was in war zone, and if had died, it seems no one would’ve cared.

It was 2007, and I was working in bloody Baqubah as a translator for the US Army. I had survived shootings and roadside bombs, I witnessed the wounding and deaths of servicemen and women—and innocent Iraqi civilians. All the memories I have from that war are indelible. But especially those of the young Russian photojournalist who died in that summer of 2007.

It was Thursday, May 3rd, just a few days before his death, that I looked out the small window of the Hummer and saw two young men approaching the convoy. I could tell they were journalists from a mile away, with their plain helmets, khaki pants and blue armored vests. , I remember exactly what I thought at that moment: “What are they doing here in Death Valley? They better not stay here for too long!”

The two men introduced themselves to the MP commander, who was sitting on the opposite side of the Hummer: Dimitry, a Russian photojournalist, and Todd, an American journalist who also worked for the AP. I was relieved when I overheard them telling the officer that they would only be in Baqubah for a few days. They easily found two seats in our convoy and off we went to a police station, where Iraqi policemen were waiting for us to set out on a joint dismounted patrol through the streets of Baqubah.

When we reached the station that day, Dimitry got out and started taking pictures of the machine gunners, two of whom were female. The commander called for a joint formation and began a briefing while I interpreted for the Iraqi policemen. The two journalists simply stood by, observing quietly from the shadow of the men in uniform from both sides.

It was my first dismounted patrol in Baqoubah Jadidah. As we walked through the deserted streets, I saw signs of the heavy toll the war had taken in my country. Hostile graffiti on the walls, wrecked and rusted-out vehicles, tree trunks blocking the streets, and piles of trash in every corner. The gravity of the war hit me hard—and I realized for the first time how dangerous it was in Diyala Province.

The Iraqi policemen, though, seemed at ease walking through their city. One posed proudly with his AK rifle for Dimitry, while Todd moved around fearlessly, Dimitry tried to capture every moment with his camera and no one tried to stop him. Some people are just fun to look at—and Dimitry, who was full of life and energy, was definitely one. His enthusiasm about his work was beyond noticeable; it was contagious. I pulled out my own camera and took a couple of pictures of him.

That evening, I saw Dimitry and Todd walking back to the tent where they were staying. As I heard their boots crunching in the gravel, I thought to myself that those two men would soon go back home with stories to tell—but the poor servicemen would stay behind in Iraq until their tour was over, constantly facing danger.

The following day, while the squad I worked for visited an Iraqi police station, we ran into the two journalists. They were sitting in the chief’s office. The colonel was a typical-looking Iraqi chief, sitting in front of his desk with dark and bumpy skin, and a thick mustache. he hid his missing front tooth by putting on a serious face and rang for the tea boy, who took a few minutes to show up. When he arrived, the chief yelled at him and the lad froze; all of us did in our seats, as he made us very uncomfortable.

I looked at Dimitry, who held a mild, neutral smile. The chief then broke into laughter and held the young boy’s wrist, saying in a soft tone, “I scared you, didn’t I?” Then he tapped him on the back, and said “Go get us tea!” We all laughed nervously at this scene out of Goodfellas—while Dimitry took advantage of the moment to snap a few shots of the menacing officer.

Dimitry and the chief communicated through body language, giving each other the thumbs-up sign, smiling and winking. The commander reached for a Skoal loose tobacco container, shook it, and put a pinch of the tobacco under his lower lip. Dimitry raised his camera. “No, no,” said the Iraqi chief pointing to his mouth. Dimitry shrugged, as if to ask “Why not?” and both burst out laughing after he had taken a few shots. Todd then said, “I’ve never seen people dipping in the US—but here everybody dips, even the Iraqis!”

Yes, the Americans taught Iraqis how to dip—and the Iraqis taught Americans how to drink sweet tea in thin, transparent demi glasses.

On Sunday I was outside the camp with the same squad when we were told to cut the mission short, but not why. I got back to the camp early enough to catch a meal at the mess hall. My friend Mona, a civilian translator, saw me from a distance, and ran up and hugged me. “I’m so glad you’re alive!” she said.

“Why, what happened?”

“I heard something bad happened, a civilian got killed…a Russian.”

When I heard the word “Russian” I collapsed onto a chair nearby and felt as though my stomach had been pierced by a knife. I covered my face with both hands and swallowed my tears knowing that my worst fears had been realized. A million thoughts bounced around in my head, starting then and recurring later; the main one was “What am I doing here?”

That night I learned that Dimitry had been killed along with six servicemen from Ft. Lewis, Washington. Their Stryker had been blown up by a roadside bomb. One so powerful that nothing was left of the Humvee, no bodies were recovered.

Over the years, the only thing that eased my sorrow over people dying in such a way was knowing that they had not felt any pain—their deaths being instant.

Dimitry and Todd had split up that day, with Dimitry choosing to hop a ride with the servicemen in their eight-wheeled armored vehicle.

After Dimitry’s death, I learned more about his life from newspapers. He had been born in Moscow in 1978. When he was 3, his parents had moved to Uganda due to his father’s career. Dimitry attended school in Canada for a few years then continued studying business administration in Russia. His college friends had nicknamed him “The Canadian.”

In a letter to a friend, Dimitry had written about his experience in Iraq and his frustration at not being able to move around there freely for security reasons. His next trip after Iraq was going to be Afghanistan.

Only death could stop such an energetic man. Sports were his passion from an early age; his favorite had been snowboarding. But a spinal injury had cut that short. His passion then shifted to photography, which led him in 2005 to cover the war in Chechnya.

He and his girlfriend had traveled to Syria on vacation, and Dimitry had fallen in love with the region. He decided to work in Beirut the summer of 2006, when Israel attacked Lebanon.

Today, after the passage of years, I still don’t dare ask if there was a use for the Iraq war. The dead are dead and the scars of those who survived will remain forever. Sometimes the memories of war haunt me, but most of the time, I chase those memories away—the stories of my days back in Iraq ten years ago.

Layla Qasrany is an Iraqi-American novelist. Her books in Arabic are Sahdoutha (2011) and Blind Birds (2016).

Click HERE to read more.

Vote for Shikha Dhingra For Mrs South Asia Canada 2017 by liking her Facebook page.

You can publish this article on your website as long as you provide a link back to this page.

Be the first to comment