Remember way, way back in November and December 2010 when Ireland was at the head of the line in the Eurozone debt crisis? Since all of the kerfuffle back then, the Irish have pretty much been given a pass on their debt by the mainstream media who, instead, have been focusing on Greece, Spain and now Portugal. I thought that given the activity regarding their PIIGS partners in recent days and weeks, that it was about time for an update on Ireland’s fiscal situation.

Remember way, way back in November and December 2010 when Ireland was at the head of the line in the Eurozone debt crisis? Since all of the kerfuffle back then, the Irish have pretty much been given a pass on their debt by the mainstream media who, instead, have been focusing on Greece, Spain and now Portugal. I thought that given the activity regarding their PIIGS partners in recent days and weeks, that it was about time for an update on Ireland’s fiscal situation.Ireland released its most recent Financial Statement in December 2011 (i.e. Budget 2012), oddly enough, on the 90th anniversary of the signing of the Treaty that restored Ireland’s sovereignty. I’ll pick out a few of the salient points for you.

Let’s take a quick look at some data first, starting with unemployment:

Since the beginning of the Great Contraction, Ireland’s unemployment has risen from just 4.8 percent in January 2008 (remember the Celtic Tiger?) to a high of 14.6 percent in April 2011. The most recent data release shows that the rate has not fallen by much and currently sits at a rather hefty 14.3 percent, above 14 percent were it has stubbornly remained for nearly a year.

Now, let’s take a look at Ireland’s debt-to-GDP ratio since 1990:

Notice that Ireland’s debt was very high in the early part of the 1990s, in part, because their economy was simply not growing. As the Celtic Tiger phenomenon developed, output (i.e. economic growth) outgrew the level of debt growth, resulting in the country’s debt-to-GDP level falling to a low of 24.8 percent in 2007. Unfortunately, that scenario was not to last. Ireland’s debt-to-GDP rose very, very quickly over the following three years to its current level of 96.2 percent.

In large part, Ireland’s current problems stem from the implosion of the country’s real estate market which, prior to the Recession, was among the fastest growing in the world. Here is a graph showing what happened to real estate prices in Ireland over the past 20 years:

Here we thought that America’s housing market readjustment was bad! Ireland experienced the largest property price increase among Europe and North American countries with values quadrupling over the period between 1997 and the peak in 2007. Nationally, average house prices have fallen to the same level that they were at in the second quarter of 2002. Some statistics show that house prices in Ireland have fallen by an average of 58 percent from their peaks, one of the worst drops in residential real estate value in the world. The drop in the value of real estate caused massive stress in the country’s banking system which, as was the case in the United States, had been only too willing to lend out mortgage money. This necessitated bank recapitalizations that totaled 32 percent of GDP, actions that the government could ill-afford as the economy ground to a halt. In the end, funding for Ireland’s banks ended up costing the ECB and Ireland’s Central Bank about €150 billion.

That’s enough background. Now let’s look at the present, keeping in mind that, according to the Eurostat website, since its inception, the European Commission has had in place a procedure called the Excessive Deficit Procedure (EDP) that would allow the EC to sanction nations whose budget deficit exceeded 3 percent of GDP and whose public debt exceeded 60 percent of GDP.

Back in December, Ireland’s Finance Minister, Mr. Michael Noonan, predicted that Ireland’s nominal GDP would grow by 2.5 percent in 2012 and states that "…all forecasters agree that growth will be significantly stronger in 2013 and subsequent years…". Not according to the IMF! He attributes this growth rate to Ireland’s very, very low corporate tax rate of 12.5 percent and is committed to keeping it low to keep the economy strong, even though he has been under international pressure to raise it. Here is a chart showing just how low Ireland’s corporate tax rate is compared to its Eurozone partners:

Ireland’s corporate tax rate is the third lowest among its fellow Member States, just below Bulgaria and Cypress (both at 10 percent) and well below the EU-27 average of 23.2 percent. Keep that and Ireland’s very high unemployment rate in mind the next time your local politician insists that your country must lower corporate income taxes so "the jobs will come". While there are other factors that have negatively affected Ireland’s economy, ultra-low corporate taxes do not seem to be a long-term job creation strategy. It is also important to note that, as Ireland’s economy imploded between 2007 and 2010, tax revenues fell by one-third, a point that should not go unnoticed by politicians around the world.

As I noted above, Ireland’s real estate sector has been decimated. The development and construction sector comprised 20 percent of GDP in the peak years and had been reduced to around 5 percent in 2011. This implosion led to the loss of 164,000 construction sector jobs. The decline in the value of residential real estate has also led to families saving rather than spending, further impacting the economy negatively. To prod the real estate market back to life, in its most recent budget, the Irish government reduced the Stamp Duty on commercial property transfers from 6 percent to 2 percent but, oddly, nothing was done to change the 1 percent Stamp Duty on property transfers up to one million euros.

The Irish government has also taken steps to address the problems facing those who purchased their properties during the height of the property boom (i.e. those who both borrowed and paid too much). For purchasers who bought their homes between 2004 and 2008, the rate of mortgage interest relief has been increased to 30 percent. For those who wish to buy a home in 2012, first time buyers will get mortgage interest relief of 25 percent and non-first time buyers will get mortgage interest rate relief of 15 percent, both up from the proposals of the previous Government. This program ends in 2018.

Ireland’s Finance Minister estimates that the deficit for fiscal 2011 will be 10.1 percent of GDP (less than the 10.6 percent required by the EU/IMF bailout agreement), down from 11.5 percent of GDP in 2010, dropping to a target of 8.6 percent in 2012. To reach the 2012 target, the government needs to cut an additional €3.8 billion in both expenditures and revenues. To meet this goal, the government held fast on not raising both personal and corporate income taxes. Back in late 2010, the previous Government agreed with the IMF and the EU that VAT would be increased by 2 percentage points by 2014. Rather than delaying the increase, the current Government will raise the VAT by the full 2 percent in 2012, raising the rate to 23 percent so that they can increase revenues much sooner.

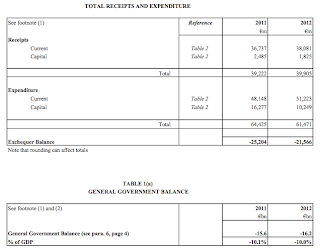

Here is a summary showing the fiscal balance for 2011 and 2012:

You will notice that in this summary, the budget deficit in 2012 is still projected to be 10 percent of GDP, just over three times the EU limit as noted above. Ireland needs the additional €3.8 billion in fiscal management as I noted above, to achieve the 8.6 percent of GDP.

Here is a graph showing how the debt interest burden in Ireland has risen in recent years with the debt interest-to-GDP ratio reaching 5 percent and consuming 14 percent of all tax revenue, up from 3.5 percent in 2007, a situation that will only become worse if the world’s bond traders lose faith in Ireland’s ability to service its debt:

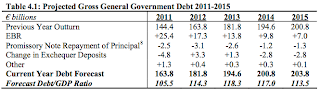

How much sovereign debt does Ireland have? In 2010, Ireland’s debt reached €144.4 billion or 92.6 percent of GDP. Debt-to-GDP levels rose between 2007 and 2010 for several reasons including large budget deficits, loss of tax revenues as the economy ground to a halt, the high cost of bailing out the country’s banking system and the significant fall in GDP from 2007 on. In 2007, general government debt was a mere €47.4 billion (25 percent of GDP). Here is a table showing the forecasted debt and debt-to-GDP figures for the period from 2011 to 2015:

Ireland’s rather stubborn debt-to-GDP ratio is projected to remain well above 100 percent of GDP over the next five years, hitting a peak of 118.3 percent in 2013, well outside of current European Community guidelines as I noted above. As well, despite reductions in deficit spending, Ireland’s overall debt will rise from €163.8 billion to €203.8 billion, an increase of 24.4 percent in just five years.

Ireland is projecting real economic growth ranging from 1.6 percent in 2012 to 3.0 percent in both 2014 and 2015. While no one can predict what will happened four years out, it most certainly would appear that the Eurozone is heading into a recession in 2012, making the 1.6 percent growth rate a less than likely projection, particularly given that GDP growth in the third quarter of 2011 was negative 1.9 percent compared to the quarter before. To increase their imports, they are also counting on G20 economic growth for the next two years of 3.8 and 4.6 percent, another highly optimistic scenario.

When summarizing all of the projections, Ireland’s government projects that the country’s deficit will fall to a low of 2.9 percent of GDP by 2015 as shown on this table, just a smidgen under the EU limit of 3 percent:

In summary, we need to remember that Ireland has already had a massive bailout totalling €85 billion and is still showing economic numbers that are not particularly great. Like governments around the world, Ireland is relying heavily on growing its way out of trouble, a highly risky proposition. They are hoping that increased tax revenues resulting from an expanding economy will help reduce the gap between revenues and expenditures and that the increase in GDP will have the added benefit of decreasing the country’s debt-to-GDP ratio. With the IMF now projecting that Europe could return to recession in 2012, all of Ireland’s hard fought battle with crippling debt could well be in vain and it is my guess that Ireland will require further assistance from the EFSF, IMF and EU. Leaders of the Free World who are spending more than you are receiving in revenue, take note! This could well be your future.

Click HERE to read more of Glen Asher’s columns.

Article viewed on Oye! Times at www.oyetimes.com

You can publish this article on your website as long as you provide a link back to this page.

Be the first to comment