If you've been awake over the past few months, you're aware that the world, particularly Europe, is suffering from a rather uncomfortable debt situation. As I posted here, it is going to be an uphill battle for the world's advanced economies to reduce their rapidly growing debt levels; the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) recently stated that to bring government debt-to-GDP ratios back to Great Recession levels, it will take 20 consecutive years of surpluses exceeding 2 percent of GDP! The odds of that – slim at best and most likely nil.

Earlier this year, the Congressional Budget Office released an interesting paper entitled "Sovereign Debt in Advanced Economies: Overview and Issues for Congress" by Rebecca Nelson. In this paper, Ms. Nelson notes that the high levels of debt among the world's advanced economies are a new global concern that has erupted out of the 2008 – 2009 global financial crisis. As we have seen, governments are embarking on fiscal austerity programs in a last ditch effort to get their books in order, however, some economists note that these measures may well undermine the very weak global economic recovery, now into its third year. As one would expect from a non-science science, other economists argue that current government austerity measures do not go far enough to rein in burgeoning debt loads, particularly as most developed nations will be experiencing top-heavy population trees.

How does all of this fit into the mandate of Congress? There are two factors to consider:

1.) Is it likely that the U.S. is headed for a Eurozone-type debt crisis? Current bond interest rates would suggest that this is unlikely, however, looking back five years, one would have never suspected that the PIIGS sovereign bonds would be suffering from interest rates in excess of 6 percent.

2.) What impact will Europe's debt crisis have on the United States economy? Slower growth in advancing economies could impact trade between America and its main trading partners. As well, in September 2011, direct U.S. bank exposure to Greece, Ireland and Portugal reached $55 billion, leaving their balance sheets somewhat vulnerable.

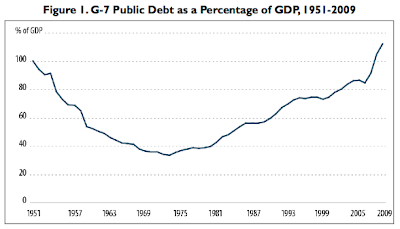

Let's start by looking at several graphs from the report. The first graph shows the changes in the gross public debt levels for the G-8 nations since the end of World War II:

The sovereign debt level for the G-7 rose from 84 percent of GDP in 2006 to a forecasted 119 percent of GDP in 2011, a 42 percent increase in just five years.

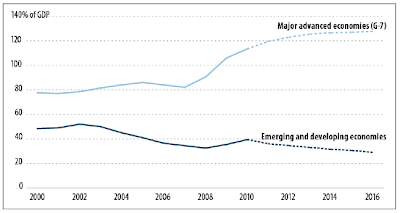

The second graph shows the gross government debt for both advanced economies and developing economies between the year 2000 and 2010, projected forward to 2016:

Sovereign debt levels for the G-7 economies rose from 84 percent of GDP prior to the Great Recession to 114 percent of GDP in 2010 and are projected to rise to 127 percent of GDP by 2016, an increase of 51 percent over 10 years. In sharp contrast, debt levels in developing economies fell from 52 percent of GDP in 2002 to 39 percent of GDP in 2010 and are projected to fall even further to 29 percent of GDP by 2016, a decrease of 44 percent over 14 years.

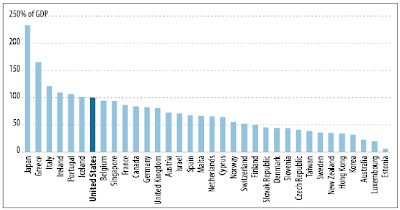

Here is a graph showing the variation of gross public debt among advanced economies in 2011:

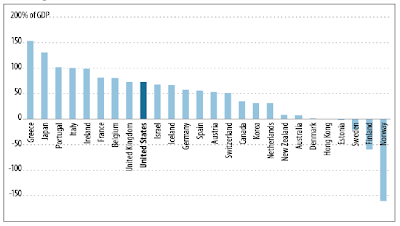

Here is a graph showing the variation of net public debt among advanced economies in 2011:

Please keep in mind that the difference between gross and net public debt statistics refer to that particular government's financial assets which are subtracted from gross public debt to give us net public debt. In the case of Japan, its gross public debt in 2010 was 220 percent of GDP but, thanks to large assets, its net public debt is "only" 117 percent of GDP. In sharp contrast, Greece's gross government debt and net government debt were both 143 percent of GDP in 2010 since the Greek government has no assets.

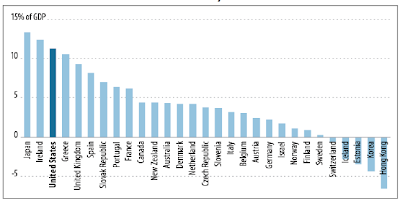

What kind of measures would be required to get this debt problem straightened out? Here is a graph showing the fiscal cuts that would be necessary to reduce debt levels to 60 percent of GDP by 2030 for the world's advanced economies:

To help you understand the preceding graph, let's look at the United States. Please note that a primary budget surplus is the budget balance excluding interest owing on the debt. The U.S. would have to achieve a primary surplus of 5.1 percent of GDP by 2020 and sustain it through to 2030 to achieve the 60 percent debt-to-GDP goal. In 2010, the primary deficit was 8.9 percent of GDP. This means that the total fiscal cuts necessary for the United States to achieve the 60 percent debt-to-GDP goal would be equal to 11.3 percent of GDP relative to the 2010 primary balance (deficit) or just under $1.7 trillion, the third highest among advanced economies after Japan and Ireland and just ahead of Greece. Now that's painful austerity!

On average, the world's advanced economies would have to reach a primary budget surplus of 3.8 percent of GDP by 2020 and sustain it through to 2030 to achieve the average 60 percent ratio. Currently, the advanced economies are running a primary budget deficit of 4.8 percent of GDP meaning that, to reach the target of 3.8 percent surplus by 2020, the average fiscal adjustment will have to be 7.8 percent of GDP.

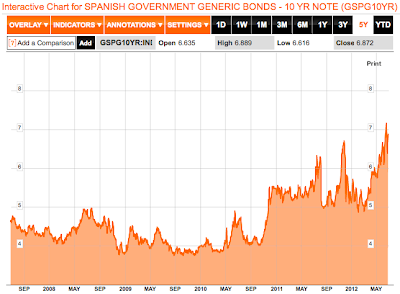

With this data in mind, why does the United States seem exempt from the wrath of the world’s debt market? The saving grace that is currently preventing the United States from becoming the next Greece, Portugal or Ireland is the fact that its currency is the world's choice for its reserves. As well, generally strong economic growth has kept the debt wolves at bay. That said, here is a graph showing how quickly Spain saw the yield on its 10 year bond rise from under 4 percent to just over 7 percent:

Basically, we cannot say that the interest rates on U.S. federal debt will never rise rapidly. At some point, the world's bond traders may simply lose confidence in the ability of the American government to continuously grow its debt, particularly if there is a repeat performance from Congress over the debt ceiling.

To summarize, the solution to the world's sovereign debt issues look rather daunting. As we've seen in Europe, the imposition of what have been until this point relatively modest austerity measures have resulted in both social upheaval and the tossing out of incumbent governments. The world's economy is already showing signs of slipping back into negative growth even with the very modest measures taken. There is one thing that I think we can count on; the next recession will be different than the recession that the world experienced in 2008 – 2009. Since sovereign debt levels were not at the sky-high levels that we are seeing today prior to the Great Recession, we are entering uncharted fiscal territory. The next global downturn could well be "The Big One".

Click HERE to read more of Glen Asher's columns

You can publish this article on your website as long as you provide a link back to this page.

Be the first to comment