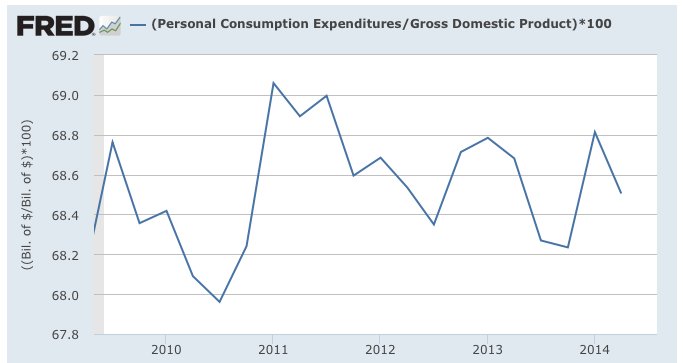

We all know that there is a close relationship between personal consumption and GDP growth as shown on this graph from FRED:

As the decades have passed, personal consumption has made up an ever-increasing component of GDP, rising from a low of 58.5 percent in 1967 to its current level of 68.5 percent. That said, if we focus on the tail end of the curve showing the data since the end of the Great Recession in June 2009, this is what we find:

It's obvious that the personal consumption component of GDP has not risen since the end of the Great Recession, unlike its pattern in since the late 1960s. Although consumer spending has risen, its contribution to GDP has not grown in the past five years.

Let's look at a brief essay by Daniel Aronson and Andrew Jordan, both at the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago that may explain why economic growth has generally been so modest since the end of the Great Recession. In their essay, the authors look at the relationship between real wage growth and the labor market. They note that there is a close relationship between the share of the labor force that is medium-term unemployed (five to twenty-six weeks of unemployment), the share that is involuntarily working part-time (less than 35 hours weekly) and real growth in wages (after inflation).

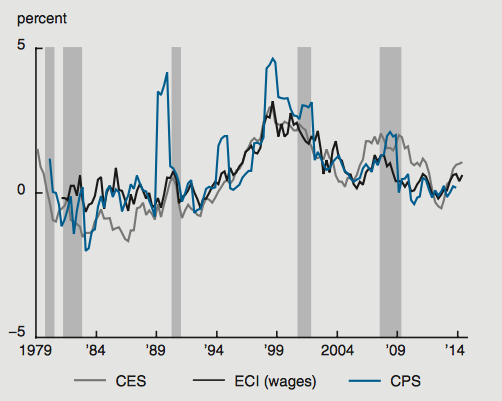

Let's start with this graph showing real hourly wage growth between 1979 and 2914:

With recessions shaded grey, we can quickly see that in the period between 1991 and 2001 during the jobs boom, real wage growth was substantial and remained above zero until around 2005. After the 2001 and 2008 – 2009 recessions, real wage growth has stalled or fallen.

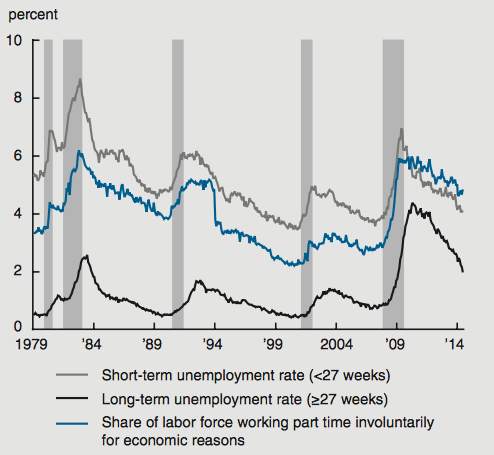

Here is a graph showing short-term unemployment (less than 27 weeks), long-term unemployment (more than 27 weeks) and involuntary part-time workers as a percentage of the workforce from 1979 to June 2014:

In the past, the national unemployment rate has been a useful predictor of real wage growth. As unemployment rose, real wage growth fell. This relationship has broken down over the past five years. Given that the unemployment rate fell from a peak of 10 percent in 2009 to 6.1 percent in June 2014, had the historical relationship between real wage growth and unemployment held, real wage growth would have been 3.6 percentage points higher by mid-2014 than it was.

Calculations by the authors show several key things for average wage earners since the end of the Great Recession:

1.) a one percentage point increase in the short-term unemployment rate results in a change in real wage growth of -0.4 percentage points.

2.) a one percentage point increase in the long-term unemployment rate results in a change in real wage growth of -0.38 percentage points.

3.) a one percentage point increase in the medium-term unemployment rate results in a change in real wage growth of -0.71 percentage points

4.) a one percentage point increase in the part-time for economic reasons underemployment rate results in a change in real wage growth of -0.40 percentage points.

As well, the authors' calculations show that the negative impact on real wage growth is higher for those that earn less meaning that the impact of the slack labor market on real wage growth is highest on those who earn the least.

The authors calculate that if labor market conditions were the same as what they were in the period between 2005 and 2007, average real wage growth would have been one-half to one percentage point higher in June 2014 than it was.

While the current job market has improved since its low point after the Great Recession, its current weakness, particularly for those that are medium- to long-term unemployed and those that are underemployed for economic reasons, is having an impact on wage growth. Without growth in wages, consumers are forced to either take on debt or reduce spending. In our consumer-oriented society, so much of economic growth hinges on never-ending increases in consumer spending and until consumers feel that they are wealthier or at least see some real growth in their wages, it will be more difficult to achieve the economic growth rates that we were accustomed to in the past.

Click HERE to read more of Glen Asher's columns

You can publish this article on your website as long as you provide a link back to this page.

Be the first to comment