What? Weren’t the ’00s, like, three years ago? Yes, yes they were. But in our rapid-paced, quickly digested world, it is possible to watch a drop in the cultural pond quickly transform into a ripple and then a wave — and we can all be witnesses (or, heck, even participants) in the process.

Earlier this year, The New York Times wondered what might induce nostalgia in 2033, and suggested that the aughts (or the naughties, if you so dare) had such a hard time defining itself because of the amalgamation of influences, zeitgeists, and world events — plus, of course, the interwebs. The piece broached a couple of interesting topics — specifically the items and objects with which the decade will be remembered — but barely grazed the surface when it came to the influences, moments, and events that, say, put the masses in a trucker hat.

According to movies and fiction, the 2000s were supposed to be the future. Instead the decade ended up being the era of whiskered, “destroyed” jeans and It items, of sweaty nightlife photography and retro American Apparel essentials. What happened to our jetpacks and flying cars? What happened to the promises of George Jetson and Hubert Humphrey?

Well, we can’t answer that. But we can take a look at what actually transpired — and why. We spoke to trend experts, editors, ’00s familiars, and archivists to trace the trends — and discuss their origins. So, take a trip down recent-memory lane and consider how we’ll remember the aughts. Warning: Some of it is good, lots of it is bad, but all of it is a load of fun.

With that out of the way, let’s start with the obvious: tech-y inspiration. Thanks to Y2K and the reemergence of pop music in an electronic format, the aughts kicked off with a total tech obsession. Metallics, sleek blacks, and a superfluous amount of straps and buckles appeared, and fashion was entirely willing to enter The Matrix. In the mainstream, bands like Destiny’s Child, Backstreet Boys, and a youngun’ named Christina Aguilera were burning up the charts. But even independent music and style were shifting toward the electronic. Silver and wet black were de rigeur; for fall ’01, Balenciaga, Calvin Klein, and Lanvin did nearly entirely black collections.

Emily Spivack, writer of Worn Stories and Smithsonian fashion archive blog Threaded, points out one totally game-changing moment: In 2001, the first iPod was introduced. “White iPod earbuds became an accessory, not just a conduit for music-listening,” she explains. “In the early 2000s, you could walk down the street and approvingly nod at other early adopters.”

Then — as anyone alive at the turn of the century can affirm — everything changed.

While September 11 certainly changed the fashion industry (and nearly every other industry) overnight, it didn’t immediately change fashion. What it did do was gradually take the edge out of the forward-blazing Y2K era. XOJane clothes editor Alison Freer astutely explains, “I think the rise of metallics in the aughts was a nod to the idea that we were entering a fabulous new millennium. But the reality of the September 11 attacks and the mortgage crisis made everyone start to crave classic, safe, comfortable looks.”

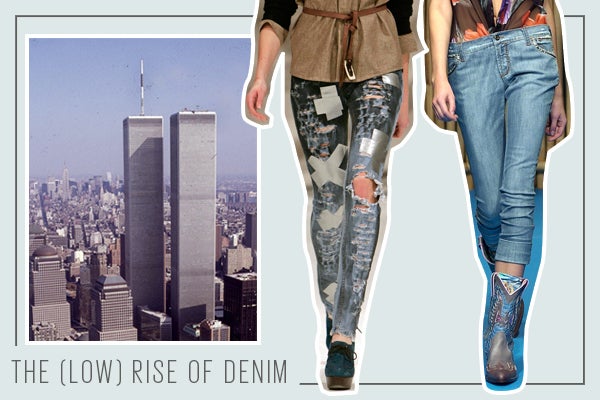

As history has shown, conservative times call for a conservative way of dressing. In America, this means returning to our good ol’ working person’s garment: jeans. U.S. womenswear editor Jaclyn Jones, from trend forecasting agency WGSN, breaks down the post-9/11 fashion reaction: “The futuristic moment had to do with Y2K and the turn of the millennium, and everyone was anticipating what that meant. But then we had 9/11. Everyone wanted to embrace American-made, American-feeling, and things we were going to wear more often. Camouflage came back into play. We began to wear selvedge and look toward Depression-era goods in order to find things less expensive or of higher quality.”

As the Times article points out, a perfectly acceptable post-work outfit was a nice top and a pair of jeans. Yet, jean trends, says WGSN’s Jones, are constantly in flux. “With jeans and pant legs, they traditionally have a trajectory that changes along with the time.” The earlier part of the aughts introduced two incredibly powerful denim trends: the super low-rise and the flair leg. Gals wanted their jeans to barely hang off their hips — think this. holy. trinity. of Britney videos. As if in reaction to the sleek, sexy, dark, and technophile movement, denim found a niche where it was impossible to look too old or worn. Sandblasted highlights and worn-in treatments lent themselves to whiskering, and whiskering appeared, well, everywhere.

In the early ’00s, however, this didn’t necessarily mean buttoning up — stability and comfort was found in labels, brands, signage, and logos. And almost every expert we spoke to agreed on one thing: The 2000s loved thrived on It items. Freer gives us her list, here. “So many handbags that debuted then are still relevant today: The Chloé ‘Paddington’ bag (2003), the Fendi ‘Spy’ bag (2005), the Balenciaga ‘Motorcycle’ bag (2001), and the Marc Jacobs ‘Stam’ bag (2005).” These weren’t just items. They were signifiers of wealth and collective agreement. Purchasing a bag meant also buying into a brand, and as Jones notes, “You have to think of Gucci at this time. Tom Ford really embraced that repeating pattern, and a big, prominent logo really took off.”

For the sake of reminiscing, Spivack gives us her list: “Kate Spade wallets; the Prada sneaker; Dior saddle bags; designer denim including True Religion low-rise, boot-cut jeans and Seven for All Mankind skinny styles; Juicy Couture velour sweatsuits; Balenciaga cargo pants; and Takashi Murakami’s collaboration with Louis Vuitton.”

Of course, It items are certainly not unique to the aughts, but never have they been so ubiquitous and identifiable. Also, for the first time, celebrity mattered. “The aughts were really the start of celebs having the power to validate fashion trends. All it took was a photo of a celeb in a trendy item and suddenly it was poppin’ off. When Paris Hilton and Nicole Ritchie wore Von Dutch trucker hats on The Simple Life, it instantly boosted the brand into the stratosphere.” Sure, we can cite iconic moments like Elizabeth Hurley’s Versace safety pin dress or Jackie O’s Cartier watch, but the average individual had previously never been able to, say, go out and purchase those weird, flat-but-oddly-comfortable boots out of Australia. What were those called again? We forgot.

The idea that Abercrombie & Fitch could charge $80 for a sweatshirt with its logo on it that people would then line up to buy it would have been unheard of before the new millennium. But, in order for brands to make money, an interesting thing happened: Luxury labels became more accessible, while mass-produced “fast fashion” dipped into the luxury space. Basically, high went lower, and low went higher, creating some easily accessible middle ground. And in America, with so many individuals having such wildly different notions of “luxury,” this mass/mainstream meld showed itself in a few interesting ways.

The practice of rap calling out fashion brands certainly isn’t new: In the ’80s, Run DMC called out “My Adidas”, and the ’90s saw numerous references to Timberlands, but these were indicators of street cred, not net worth. When the millennium rolled around, rappers seriously increased their fashion repertoire — not just for social validation, but as proof of affluence and access. Says Freer, “Rappers started lavishing cash on name brand, luxury fashion. Suddenly an entirely new segment of the population became luxury goods consumers.” She then adds, “The intersection of fashion and hip-hop was the biggest style story of the aughts. I worked on a dozen Roc-A-Fella music videos from 2003-2007, and have the Rocawear velour track suits to prove it.”

Streetwear became casualwear and casualwear became ubiquitous. A hoodie, loose-fitting jeans, and hoop earrings seemed to span races, cultural identifiers, income, and location, and suddenly, being “label-fluent” was a sign of caché. “There was an entirely new segment of the population that became luxury goods consumers. Magazine editors were no longer the only fashion know-it-alls,” Freer remarks.

Yet, the pinnacle of luxury for the masses kicked off in 2002, with the newest iteration of the bridge line: the designer collab. And that concept is still going strong in 2013. When Isaac Mizrahi launched for Target in ’02, we witnessed the first such collaboration. Then came Pierre Hardy for Gap, Proenza for Target, Karl Lagerfeld for H&M, Jil Sander For Uniqlo, Rodarte for Target…the list goes on and on. Even indies like Prabal and Odin have teamed up with a Big Box by now. The logical next step in diffusion.

Perhaps it was 9/11, or the residual effects of Sex & The City, or The Devil Wears Prada, or the rise of The Strokes, but New York City was a major cultural playing in the aughts. Yet, with rising rents and a mortgage crisis, the borough over the bridge became a real influencer. The idea of going to a party in Brooklyn was, despite what Gossip Girl might suggest, not unthinkable.

“Simultaneous with — and perhaps in response to — fast fashion, came a push for more sustainable clothing from the past, re-imagined for the present. The credit crunch led to the adoption of things like DIY, crafting, recycling, up-cycling, thrifting, and Etsy,” Emily Spivack says. The general move to Brooklyn seemed to echo a nationwide shift, away from labels and status and toward the (get ready for it) “hipster.”

Before we all freak out about the usage of the “h”-word, let’s be clear: We mean a more retro-inspired, thrift-friendly, irony-imbued style — and the sudden tight pant silhouette. The trend pendulum swung to the other end; It items that everyone had were replaced with vintage or classic labels, luxury was swapped out for cheeky effortlessness. What people wore was less influenced by celebrities, and more influenced by real people — thanks to the rapid sharing potential of the Internet.

Friendster, MySpace, and Facebook became instant ways to share outfits or haircuts, but thanks to sites like Mark Hunter’s Cobrasnake, it was suddenly possible to share scenes, too. “When I started the website, I just wanted to capture the feeling I got when I would go to shows. It turned out that a lot of people liked that feeling as much as I did, and the site has just evolved from there,” Hunter says. “Just on a basic level, one of the most fun parts about going out is looking at what people are wearing and how hot they look, and a photo website is kind of perfect place to share that.” Also, sites like Last Night’s Party, Nicky Digital, and The Misshapes showcased the places where urban dwellers could see and be seen. That bright, messy, off-the-cuff and hedonistic style became unmissable, whether in the Cobrasnake, Terry Richardson, or the ultra-recognizable American Apparel ad.

So, here’s the real question: Why do we have such a love-hate relationship with the most recent decade we all lived through, from BritBrit to trucker hats to hipsters? Particularly when we’re all so fond of looking back at, say, the ’90s.

No really, think about it: The currently featured exhibit at the New Museum in New York is entitled “NYC 1993: Experimental Jet Set, Trash and No Star,” and it reflects exclusively on the significance of 1993. Well, our present-day interest in the ’90s — a moment that is totally pervasive in contemporary fashion — feels pretty neatly dictated by Laver’s Law, which states that the lifecycle of a fashion trend covers five stages: the one in which it feels smart and of-the-moment, followed by the one in which it feels dowdy, then hideous, then amusing, and finally, over the course of many years, romantic. (Of course, in recent years, the Laver cycle has shortened dramatically.)

That means that the ’90s, for us, are currently toeing the line between charming and romantic. And the early, aughts, in turn, feel pretty darn painful to look back on, aesthetically speaking (ahem, this red carpet situation happened). However, we’d venture to say that, back in belly-baring ’03, recalling ’93 might have also felt pretty unfortunate as well, with its awkward-length skirts and shabby flannel. Cycles — so predictable.

Click HERE to read more from Refinery29.

Be the first to comment