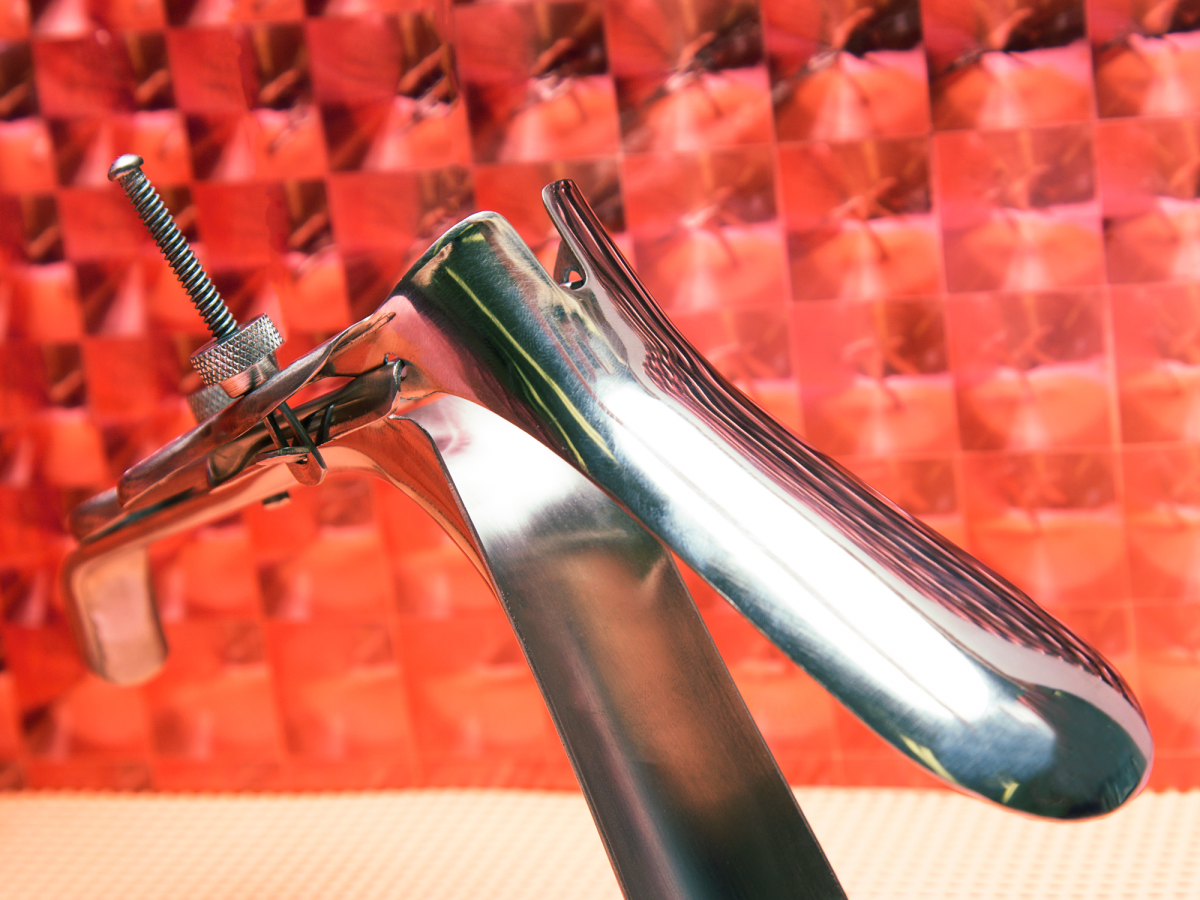

Photographed by Tayler Smith.

Thanks to everyone’s least favorite screening test — the pap smear — cervical cancer has gone from being a leading cause of death in young women in the 1940s to being one of the most preventable and curable cancers today. That is, if you identify as straight and cisgender.

While our cancer registries do not tally cancer incidence or deaths by sexuality and gender identity, it has long been known that lesbian, bisexual, and queer (LBQ) women, as well as transgender men, are less likely than their straight and cis counterparts to be screened for cervical cancer. (And that the majority of cases of cervical cancer diagnosed today occur among people who do not get screened.) Some studies estimate that just 43% of LBQ women get regular cervical screening, compared to 73% of straight women. A 2012 report found that roughly half of transgender men say they postpone or skip regular preventative-care visits, including cervical screenings.

Many people face barriers to obtaining adequate reproductive health care, including all-important factors like cost and insurance, but LBQ women and transgender men often deal with the added (and infuriating) burdens of stigma, discrimination, and a lack of awareness among medical professionals about LGBTQ-specific health issues, according to troubling new research published in the journal Cancer Nursing.

For this study, researchers wanted to understand why exactly these women and men tend to skip cervical screenings, so they recruited and interviewed roughly 250 LBQ women and trans men between the ages of 21 and 65. Most of the participants in this study actually were “routine cervical cancer screeners,” but even then “many described how LBQ women avoid pap tests because they fear being judged or discriminated against,” the researchers reported. They also found that mistrust of doctors and the healthcare system on the whole often prevented some people from seeking screening, even if they were aware it was recommended.

These results are unsurprising to Signey Olson, a nurse practitioner in Washington, D.C., who specializes in gynecological care and family planning for LGBTQ patients. “Many patients encounter outright hostility and trans- or homophobic treatment,” she says. “As such, these individuals may be understandably afraid to seek care, even when they need it.”

Alaina Leary, a 23-year-old bisexual and queer woman who lives in Boston, says she often skips routine screenings because she’s had traumatic experiences with medical staff. “I’m always worried that medical professionals won’t take my experiences seriously,” she says.

“I’ve definitely avoided routine check-ups. I’m 23 and I’ve only had one pap smear and one gynecological visit.”

Her mistrust started when she went to the campus health center in college after a sexual assault. “They automatically gendered my attacker as a ‘he’ and seemed confused, like they didn’t believe a female could rape someone or pass an STI on to me,” she says. “I’ve had medical professionals dismiss the idea that rape by a female was as dangerous, physically or emotionally, or that it could even happen at all.” Soon Leary found herself educating the medical staff on basic sexual health, a burden that was especially overwhelming given the already traumatic circumstances.

Since then, “I’ve definitely avoided routine check-ups,” Leary explains. “I’m 23 and I’ve only had one pap smear and one gynecological visit.”

For trans men, the frustration of facing stigma and misinformation can be compounded by gender dissonance. As one trans participant in the study reported, “For trans men, needing to focus on an essential female part of themselves is incredibly upsetting.”

Parker, 23, a trans man from Minnesota, says that simply entering an ob-gyn office used to cause a lot of anxiety. “I was hesitant to go to the ob-gyn because I was afraid of the looks I would get while sitting in the office, as well as how the staff would react to scheduling someone with a male name,” he says. Parker delayed cervical cancer screenings until he was required by his surgeon to have one prior to a hysterectomy.

Though apprehensive about going to the gyno, Parker understood that it was important. “Although it made me anxious to get a pap smear, I valued my health over what the doctor’s reaction would be,” Parker says.

In the end, Parker’s experience was way better than he expected it to be. “My first and only pap smear was uncomfortable, but not because of my doctor,” Parker explains. “I was uncomfortable due to my gender identity. But my doctor talked me through the entire procedure, so I knew what was going on and why.”

Although not every trans person decides to have gender-affirming surgeries, these intimate decisions are another thing made easier with the help of understanding and inclusive doctors. In addition, people who have hysterectomies generally eliminate the risk for cervical cancer, so this procedure allows some trans and non-binary people to sidestep the problems presented by future screenings.

Simply respecting a patient’s identity and giving them autonomy over their body and examinations, as Parker’s doctors did, can make a world of difference, Olson explains. But sadly, Parker’s experience is not the norm: According to data from the National Transgender Discrimination Survey, many transgender people have trouble finding providers who are sensitive to these specific needs. For instance, 19% of survey respondents reported being denied medical care when sick or injured due to discrimination; 28% reported harassment in medical settings. Half of all respondents reported having to teach their medical providers about transgender-specific needs.

What’s more, when it comes to cervical cancer screenings in particular, having a doctor who understands transgender health may be especially important: A 2014 study found that trans men are more likely to have “inadequate” pap smear results, meaning the samples taken from patients were more likely to be unusable, leading to a need for repeated exams. The researchers concluded that this was both due to discomfort and because trans men who take hormones may experience physical changes to the cervix that make getting a sample more difficult. What could help? “Clinicians should receive training in increasing comfort for [trans] patients during the exam,” the researchers wrote.

There is such a need for more clinicians who understand these barriers and who intentionally create safe spaces for people who have previously been mistreated or neglected by our system.

As frustrating as this is, there are small signs of progress for those in need of queer-inclusive care. In 2014, for example, the Association of American Medical Colleges released new guidelines for better preparing young doctors to care for LGBTQ as well as intersex patients. The hope is that training doctors early on to understand these issues can help.

As for finding a currently practicing physician who is queer-friendly and queer-inclusive, LGBTQ people have an excellent resource in the Health Professionals Advancing LGBT Equality (previously known as the Gay & Lesbian Medical Association) database, where individuals can search for LGBTQ-friendly providers. Many queer people also seek their local LGBTQ community centers for references.

Still, as of now, there remains a dearth of providers, depending on where you are. A search of the database for queer-inclusive doctors in the state of Alabama, for example, returns a grand total of six providers, three of whom are therapists. None is a gynecologist. Compare this to New York state, where there are 292 providers to choose from in varying specialties.

Surely, there are competent doctors who don’t know how to reach out to LGBTQ patients, but not knowing whether your doctor is queer-friendly presents challenges as well. Leary’s primary-care doctor has been supportive of her sexual orientation, for example, but the process of coming out to a new medical professional is frightening. “I’m always wary about getting a new doctor because I’m worried about queer antagonism in the field,” she says. And this fear can cause queer people to avoid seeking not just pap smears, but also other screenings, STI tests, and rape kits.

As Olson stresses, it’s important for all medical professionals to pay more attention to the needs of the LGBTQ community. “There is such a need for more clinicians who understand these barriers and who intentionally create safe spaces for people who have previously been mistreated or neglected by our system,” she says.

A trip to the gyno’s office might never be pleasant. From scheduling the appointment to answering questions about your sexual history, interacting with the healthcare system often leads to feelings of vulnerability, discomfort, and even fear, no matter who you are. But many heterosexual, cis people have access to a doctor who understands these fears and can provide a safe space. And that experience should be universal.

Click HERE to read more..

You can publish this article on your website as long as you provide a link back to this page.

Be the first to comment