A set of recently released documents provides us with some significant insight regarding the direction that the United States planned to take after the collapse of the Soviet Union. The first document is dated August 17th, 1992 and was authored by two scientists, Thomas W. Dowler and Joseph S. Howard II, at the Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico. The second document with less detailed information is dated December 18 – 19, 1991 and was a briefing overview delivered to the Joint Defense Policy Board and the Defense Science Board Task Force on Non-Strategic Nuclear Forces or NSNF.

Let’s look at the document from 1992 first. In their paper, Dowler and Howard note that the post-Soviet world is a far different place and that there is a growing potential for a “wide spectrum of regional conflicts”. In this new post-Cold War global reality, the two scientists note that there will be a requirement for a new type of low-yield nuclear weapon that have the capability to “deter well-armed tyrants” among others. The actors observed that, while the United States will maintain its presence in the world as a major owner of strategic nuclear weapons, the drawdown in the numbers of servicemen and women in the Armed Forces will affect the type of combat that the United States is used to fighting. It is important to keep in mind that, at the same time as this research was ongoing, in September of 1991, President Bush I announced that the United States would eliminate its inventory of ground-launched, short-range nuclear weapons including Army and Marine nuclear artillery shells and Lance missiles. In addition, the Bush I Administration committed to bring the Navy’s inventory of tactical nuclear weapons back to the United States. At the time, the authors projected that the national nuclear weapon inventory would contain 3500 strategic nuclear weapons and 1600 tactical nuclear weapons, all of which are designed to deter or win a war against the Soviet Union. To provide America with the weaponry needed to both deter and fight a war, the authors spent 18 months focussing not he development of low-yield nuclear weapons for the following reasons:

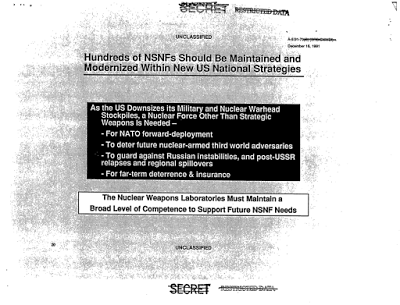

1.) Provision of stability, insurance and deterrence by maintaining America’s leading role in the continued development of nuclear weaponry.

2.) Meet America’s forward-deployed commitments to NATO with the goal of continuing to provide stability to Europe.

3.) Added insurance against a resurrected threat posed by a resurrected Soviet Union.

4.) Deterrence for nuclear-armed third-world nations.

The authors focussed on the use of low-yield nuclear weapons as a point of deterrence. These very low-yield nuclear weapons could be used to protect U.S. forces during the early stages of a deployment when conventional forces are still highly vulnerable to attack by a third world nation. They note that the use of such low-yield weapons would result in far less political cost to an American administration than the use of a high-yield weapon that would result in the destruction of vast urban areas. The authors use the example of Operation Desert Storm; had Saddam Hussein attacked with all of his forces before the coalition had time to get its forces in theatre, the United States may have found itself choosing between the loss of a division of soldiers and the deployment of a strategic nuclear weapon which would have caused a disproportionate level of collateral damage. By having a low-yield, low-collateral damage weapon, the United States would provide itself with an option that is militarily advantageous at the same time as it causes relatively little collateral damage.

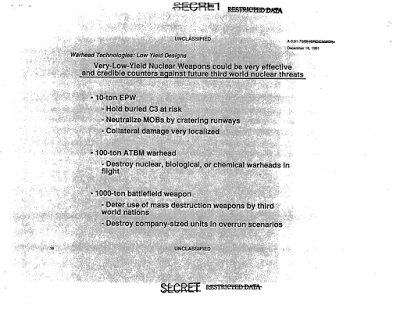

What kind of weapons are we discussing? The authors have three classifications of low-yield nuclear weapons:

1.) Micronukes – have a yield equivalent to 10 tons of high explosive

2.) Mininukes – have a yield equivalent to 100 tons of high explosive

3.) Tinynukes – have a yield equivalent to 1000 tons of high explosive

By way of comparison, the bomb that devastated Hiroshima had a yield of approximately 15 kilotons (i.e. 15,000 tons) of explosive and the bomb that devastated Nagasaki a few days later had a yield of approximately 20 kilotons (i.e. 20,000 tons) of explosive.

The authors then look at the possible roles for micronukes. Micronukes could be effective in several scenarios:

1.) destroy leaderships facilities and command centres that are too deep to be destroyed by conventional weapons.

2.) crater enemy runways and destroy enemy air forces which would prevent enemy air operations from taking place.

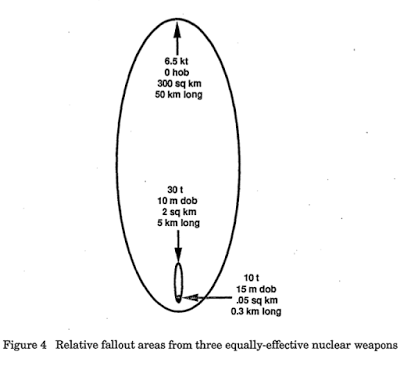

Since these micro weapons have very low yields, the radioactive fallout resulting from their detonation would be minimal; a 10 ton weapon buried at 15 metres would have a fallout area of only 0.05 square kilometres and a 30 ton weapon buried at 10 metres would have a fallout area of only 2 square kilometres as shown on this graphic from the paper:

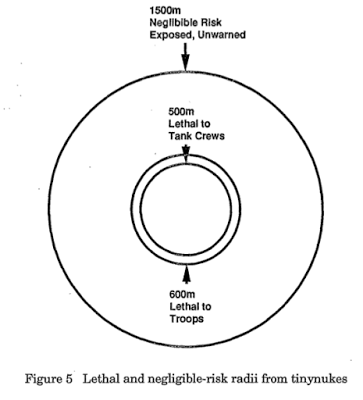

Tinynukes could be used to deter an enemy attack in the case where enemy forces outnumber U.S. forces. The lethal radii from a tiny nuke is still small but its lethal radius is still substantial enough that it would result in far less effective enemy forces as shown on this graphic from the paper:

The fallout from a tiny nuke could cover as much as 60 square kilometres and extend nearly 20 kilometres downwind from the airburst location.

The authors close their paper with this paragraph:

“We believe that the long-term nuclear stockpile of the US should include several hundred low-yield nuclear weapons. These weapons would help provide long-term stability and deterrence against world-wide contingencies, as well as insurance against technological surprises. They could be used to meet our forward-deployed commitments to NATO and to provide insurance against any possible resurrection of a tactical nuclear threat from the former Soviet Union. But their mail role would be to help deter aggression by future third-world nuclear states.”

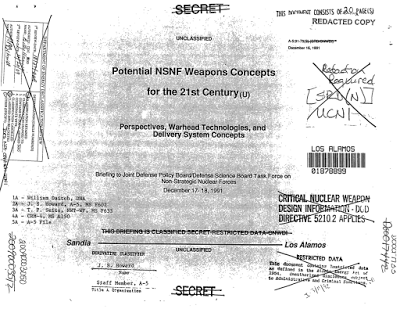

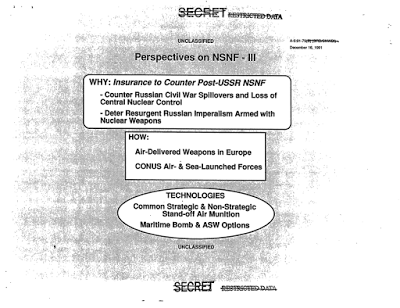

Now, let’s take a brief look at the briefing overview given to the Joint Defense Policy Board and the Defense Science Board Task Force on Non-Strategic Nuclear Forces in December 1991. Here is the title page of the heavily redacted document:

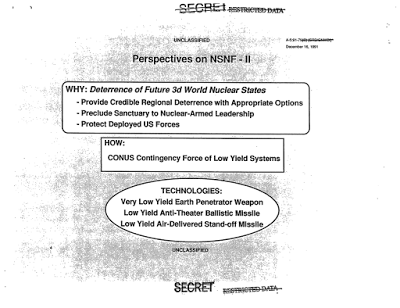

Here are the pages showing the goals of the Non-Strategic Nuclear Forces:

Here are the pages showing the categories of low-yield nuclear weapons and the rationale behind using them:

These recently released documents provide us with an interesting insider’s glimpse at the mindset of the Department of Defense and the Department of Energy’s facilities at Los Alamos. Even with the possibility of political backlash that would face the administration that chose to use nuclear weapons in any form, for the Pentagon, it was full steam ahead when it came to unleashing the power of the atom. In this time of a resurrected anti-Russian stance by Washington and a Russia that is flexing its military muscle is that this research into micro nuclear weapons could well become increasingly pertinent to the war mongers in the hallowed halls of the American federal government.

Click HERE to view more.

You can publish this article on your website as long as you provide a link back to this page.

Be the first to comment